Business Models in Waste Management: Which Partnership Schemes Work in Indonesia?

Waste Management Partnership Schemes: Comprehensive Analysis of Business Models for Indonesian Market

Reading Time: 42 minutes

Key Highlights

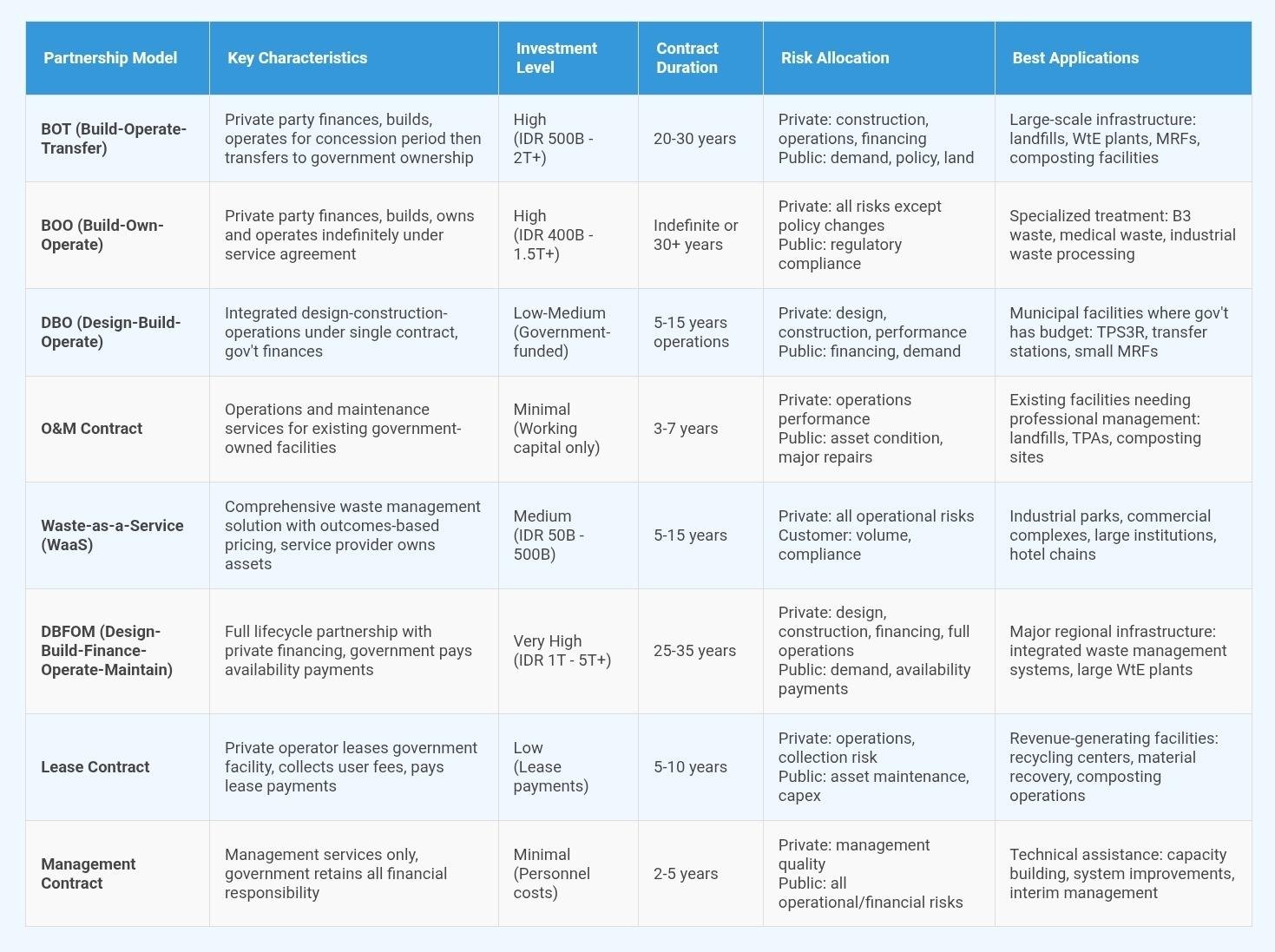

• Multiple Partnership Models: Indonesia waste management sector supports diverse business schemes including BOT (Build-Operate-Transfer), BOO (Build-Own-Operate), DBO (Design-Build-Operate), O&M contracts, and emerging Waste-as-a-Service models, each offering distinct risk allocation, financing structures, and operational responsibilities

• Market Size and Opportunity: National waste generation reaching 68 million tons annually with less than 70% receiving proper management creates substantial business opportunity estimated at IDR 150-200 trillion through 2030 for collection, processing, and disposal infrastructure and services

• Regulatory Framework: UU No. 18/2008 on Waste Management and supporting regulations including Perpres 38/2015 on KPBU (Public-Private Partnerships) provide legal foundation for private sector participation across municipal solid waste, industrial waste, and hazardous waste management segments

• Risk-Return Profiles: Partnership schemes vary substantially in investment requirements (IDR 50 billion to 1+ trillion), contract duration (5-30 years), revenue mechanisms (tipping fees, gate fees, service fees, product sales), and risk allocation determining optimal model selection for specific contexts

Executive Summary

Indonesia's waste management sector presents substantial business opportunities driven by rapid urbanization, growing waste generation reaching 68 million tons annually, regulatory mandates for improved waste handling under UU No. 18/2008, and increasing awareness of environmental impacts from inadequate waste systems.1 Current national waste management capacity serves less than 70% of generated waste properly, leaving significant gaps in collection, processing, recycling, and disposal infrastructure requiring estimated investment of IDR 150-200 trillion through 2030 to achieve national targets and meet service demand from expanding urban populations. These infrastructure and service gaps create diverse business opportunities across municipal solid waste, commercial and industrial waste, hazardous waste, and specialized streams including medical waste, construction waste, and electronic waste.

Multiple partnership schemes enable private sector participation in waste management spanning full spectrum from simple service contracts to complex infrastructure concessions. Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) arrangements involve private partners financing, constructing, and operating waste facilities for 20-30 year concession periods before transferring assets to government ownership, suitable for major infrastructure including landfills, material recovery facilities, and waste-to-energy plants requiring substantial capital investment. Build-Own-Operate (BOO) models provide permanent private ownership of waste facilities with indefinite operating rights under long-term service agreements, appropriate when government prefers avoiding future asset management responsibilities. Design-Build-Operate (DBO) combines design, construction, and operations under single contract typically spanning 5-10 years, offering integrated delivery with performance accountability. Operations and Maintenance (O&M) contracts provide operating services for government-owned facilities, requiring minimal private investment while delivering operational expertise. Emerging Waste-as-a-Service models offer comprehensive waste management solutions with outcomes-based pricing, transferring operational and performance risk to service providers while providing predictable costs for customers.

Indonesian regulatory framework established through UU No. 18/2008 on Waste Management and Presidential Regulation No. 38/2015 on KPBU (Kerjasama Pemerintah dan Badan Usaha or Public-Private Partnerships) provides legal foundation and procedural guidance for structured private sector participation in waste infrastructure and services. These regulations define permissible partnership structures, procurement procedures, risk allocation principles, government support mechanisms, and performance monitoring requirements creating predictable framework for investment while protecting public interests. Ministry of Finance KPBU unit provides implementation support including project preparation facilities, transaction advisory services, viability gap funding for marginal projects, and government guarantees mitigating specific risks hindering private investment in strategically important waste infrastructure.2

This comprehensive analysis examines partnership schemes applicable to Indonesian waste management sector, comparing BOT, BOO, DBO, O&M, and Waste-as-a-Service models across dimensions including investment requirements, contract duration, risk allocation, revenue mechanisms, regulatory requirements, and suitability for different waste management applications. Discussion incorporates international frameworks adapted to Indonesian context, successful implementation cases demonstrating model viability, financial structuring considerations, risk mitigation strategies, and decision criteria supporting optimal model selection for specific circumstances. Real-world case studies illustrate application of different partnership approaches to municipal solid waste management, industrial waste services, and material recovery operations, providing practical insights for businesses evaluating market entry or expansion strategies in Indonesia's growing waste management sector.

Comprehensive Partnership Schemes Comparison Matrix

Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) Model Analysis

Build-Operate-Transfer arrangements represent most common partnership structure for major waste infrastructure projects requiring substantial capital investment and long operating periods for financial viability. Under BOT scheme, private sector partner or consortium finances project development including land acquisition if needed, designs and constructs facilities meeting specified technical and environmental standards, operates infrastructure for concession period typically spanning 20-30 years recovering investment through user fees or government payments, and transfers ownership to government at concession end with assets in agreed condition. This model enables government to procure large-scale infrastructure without upfront capital expenditure while benefiting from private sector efficiency in project development and operations, though government bears long-term payment obligations and ultimate facility ownership requiring lifecycle planning.

BOT model proves particularly suitable for capital-intensive waste infrastructure including sanitary landfills requiring cell construction, leachate treatment, gas management, and environmental monitoring; material recovery facilities with mechanical sorting, biological treatment, and residue management capabilities; waste-to-energy plants utilizing combustion, gasification, or anaerobic digestion technologies; and integrated waste management facilities combining multiple treatment and disposal functions. These projects typically require IDR 500 billion to over IDR 2 trillion investment depending on capacity and technology, warranting 20-30 year concession periods enabling private partners to recover investment plus reasonable returns while providing government long-term waste management solutions. Successful BOT implementation requires careful risk allocation addressing demand risk through minimum volume guarantees or take-or-pay obligations, technology risk through proven technology selection and performance standards, financing risk through government support or guarantees, and regulatory risk through clear contractual frameworks establishing rights and obligations.

BOT Model Key Elements:

Contract Structure and Duration:

• Concession agreement: 20-30 years typical for waste infrastructure

• Design and construction period: 2-4 years depending on project scale

• Operations period: 16-28 years generating revenues covering investment and returns

• Transfer provisions: Asset condition requirements, training, documentation handover

• Extension options: Possible if mutual agreement on terms and conditions

• Early termination: Compensation mechanisms for government or private party termination

Financial Arrangements:

• Private financing: 70-80% debt, 20-30% equity typical capital structure

• Revenue mechanisms: Tipping fees, gate fees, government availability payments

• Minimum volume guarantees: Government commits minimum waste quantities

• Tariff escalation: Annual adjustments for inflation, fuel costs, currency fluctuations

• Refinancing gains: Sharing mechanisms for cost reductions or improved terms

• Government support: Viability gap funding, guarantees, land provision

Risk Allocation Matrix:

• Construction risk: Private party responsible for completion, cost overruns, delays

• Operations risk: Private party ensures performance meeting output specifications

• Technology risk: Private party selects proven technology meeting guarantees

• Demand risk: Shared through minimum guarantees and private marketing efforts

• Regulatory risk: Government responsible for permitting, policy changes

• Force majeure: Shared based on event nature and impact

Performance Requirements:

• Technical standards: Output specifications, environmental compliance, safety

• Service availability: Minimum uptime requirements, maintenance schedules

• Environmental performance: Emissions limits, effluent quality, solid residue disposal

• Reporting obligations: Monthly operations reports, financial statements, audits

• Performance bonds: Financial security ensuring contract compliance

• Penalties and incentives: Payment adjustments for performance variations

Indonesian BOT waste projects demonstrate model viability though implementation remains limited relative to sector needs. Notable examples include several regional integrated waste management facilities under development through KPBU frameworks, though many projects face delays from permitting challenges, land acquisition difficulties, tariff negotiation complexities, and financing constraints. Successful implementation requires strong government commitment including adequate budget allocation for payments, realistic demand projections avoiding optimism bias, appropriate risk sharing rather than attempting full risk transfer to private sector, and professional project preparation addressing technical, financial, legal, and environmental aspects before procurement. Ministry of Finance KPBU unit and project preparation facilities provide technical assistance supporting local governments developing bankable waste infrastructure projects suitable for private sector participation through BOT or similar partnership structures.

Build-Own-Operate (BOO) Model Framework

Build-Own-Operate model provides alternative to BOT enabling permanent private ownership of waste facilities with indefinite operating rights under long-term service agreements with government or commercial customers. Unlike BOT where assets transfer to government at concession end, BOO operator retains ownership throughout facility lifetime typically exceeding 30-40 years, eliminating transfer obligations while requiring private party to manage asset renewal and eventual decommissioning. This arrangement proves attractive when government prefers avoiding future asset ownership and management responsibilities, when revenue certainty supports indefinite private operations, or when specialized facilities serve primarily commercial markets rather than universal public service obligations requiring eventual government control.

BOO model finds particular application in specialized waste treatment facilities including hazardous waste treatment centers serving industrial clients under regulatory mandates, medical waste incinerators processing healthcare facility waste requiring specialized handling, industrial wastewater treatment plants serving manufacturing operations, chemical waste neutralization facilities, and material recovery operations generating revenues from recyclable commodities. These applications share characteristics of serving defined customer bases willing to pay service fees covering costs plus returns, utilizing specialized technologies requiring ongoing expertise beyond typical government capabilities, and operating in competitive or semi-competitive markets where permanent private ownership aligns with commercial dynamics. Capital requirements range from IDR 400 billion to over IDR 1.5 trillion depending on facility scale, treatment technology, and environmental protection systems required for regulatory compliance.

BOO Model Distinctive Features:

Ownership and Asset Management:

• Perpetual private ownership: No transfer obligation to government

• Long-term asset planning: Private party manages full lifecycle including replacement

• Residual value: Private operator retains asset value at end of useful life

• Expansion rights: Operator can upgrade or expand capacity meeting demand growth

• Asset disposal: Private party responsible for eventual decommissioning

• Collateral value: Assets serve as security for project financing

Service Agreement Structure:

• Long-term contracts: 15-25 years with government or anchor customers

• Automatic renewal: Provisions for contract extension if performance satisfactory

• Service specifications: Output requirements, quality standards, compliance obligations

• Pricing mechanisms: Fee structures covering operations, capex recovery, returns

• Volume commitments: Minimum or exclusive waste supply agreements

• Termination: Limited to breach, with compensation for asset value

Market and Commercial Considerations:

• Customer diversity: Multiple customer streams reducing dependency risk

• Competitive positioning: Differentiation through service quality, reliability, compliance

• Commodity risk: Exposure to recyclable material price volatility

• Regulatory compliance: Meeting evolving environmental and safety standards

• Technology refresh: Private incentive to adopt improvements maintaining competitiveness

• Market evolution: Adapting to changing waste streams and treatment requirements

Risk Profile Comparison to BOT:

• Higher private risk: Full asset ownership and performance responsibility

• Longer horizon: No fixed transfer date creating indefinite commitment

• Greater flexibility: Private control enables operational and strategic decisions

• Returns potential: Upside from efficiency gains, capacity expansions, market growth

• Government perspective: Transfers lifecycle asset management burden

• Public oversight: Continued through environmental permits and service standards

BOO model implementation in Indonesia remains relatively limited compared to BOT though growing in specialized waste segments particularly hazardous industrial waste and medical waste treatment where private sector expertise and facility specialization create natural fit for permanent private ownership. Regulatory framework under UU No. 18/2008 and sector-specific regulations for B3 hazardous waste management accommodate BOO arrangements through licensing and permitting systems governing facility operations rather than ownership structures. Key success factors include securing long-term customer contracts or waste supply agreements providing revenue certainty, obtaining appropriate environmental permits including AMDAL (environmental impact assessment) and operating licenses, developing strong customer relationships through reliable service and regulatory compliance support, and maintaining technical capabilities adapting to evolving treatment technologies and regulatory requirements over extended facility lifetimes.

Design-Build-Operate (DBO) Integrated Delivery

Design-Build-Operate approach combines facility design, construction, and operations under single contract with unified responsibility, though unlike BOT/BOO models, government typically provides financing rather than relying on private capital. DBO contractor prepares detailed design meeting functional requirements, constructs facility to design specifications, commissions systems verifying performance, and operates infrastructure for defined period typically 5-15 years under performance-based compensation. This integrated delivery offers several advantages over traditional design-bid-build approaches including single-point accountability eliminating interface risks between designers and constructors, design optimization incorporating operational considerations and lifecycle costs, faster project delivery through overlapping design-construction activities, and operations feedback improving design quality through contractor's direct operational responsibility incentivizing practical, maintainable solutions.

DBO model suits waste management applications where government has available capital or secured financing but seeks to transfer design, construction, and operations risks to experienced private sector partners. Typical applications include municipal material recovery facilities processing residential waste streams with mechanical sorting and biological treatment, transfer stations consolidating waste for efficient transport to disposal sites, TPS3R facilities providing reduce-reuse-recycle services at neighborhood scale, composting facilities processing organic waste from markets and households, and small-to-medium sanitary landfills serving towns or districts with limited technical capacity. Investment scales range from IDR 50-500 billion depending on facility type and capacity, with government financing through budget allocations, infrastructure bonds, or development bank loans while contractor provides expertise and performance guarantees rather than capital.

DBO Contract Framework:

Design Phase Deliverables:

• Performance specifications: Output requirements, treatment efficiency, capacity

• Design development: 30% preliminary, 70% detailed, 100% construction drawings

• Technology selection: Proven systems meeting performance and cost objectives

• Environmental compliance: AMDAL, permits, mitigation measures

• Construction planning: Schedule, logistics, quality assurance program

• Operations planning: Staffing, procedures, maintenance programs, spare parts

Construction Phase Requirements:

• Fixed-price obligation: Contractor bears cost overrun risk

• Schedule guarantees: Liquidated damages for delays

• Quality standards: Materials, workmanship per specifications and codes

• Safety requirements: Construction safety plan, incident prevention

• Progress reporting: Monthly updates, milestone achievements

• Commissioning tests: Performance verification before handover to operations

Operations Phase Management:

• Performance standards: Throughput, efficiency, environmental compliance

• Service availability: Minimum uptime requirements, planned maintenance windows

• Reporting obligations: Daily operations logs, monthly performance reports

• Maintenance responsibility: Preventive and corrective maintenance

• Major repairs: Shared responsibility based on contract terms

• Technology upgrades: Provisions for improvements during operations period

Compensation Structure:

• Design-build payment: Milestone-based during construction, retention held until completion

• Operations payment: Fixed monthly fee plus performance-based incentives/penalties

• Performance incentives: Bonuses for exceeding targets (efficiency, availability, quality)

• Performance penalties: Deductions for failures or non-compliance

• Extraordinary events: Adjustments for force majeure or government-caused delays

• Payment security: Government budget commitment, escrow accounts

DBO procurement typically follows competitive process where government issues functional requirements and performance specifications rather than prescriptive designs, allowing contractors to propose optimal solutions balancing capital costs against operational efficiency and lifecycle considerations. Evaluation criteria weight technical approach, relevant experience, operations plan, and price, with emphasis on proven experience and realistic operational cost projections rather than merely lowest construction cost. Indonesian government agencies increasingly adopt DBO for waste projects supported by Ministry of Public Works and Housing technical guidance, though implementation challenges include developing appropriate performance specifications, evaluating lifecycle cost proposals requiring specialized expertise, and monitoring contractor performance throughout extended operations periods requiring dedicated government oversight capacity.

Operations and Maintenance (O&M) Service Contracts

Operations and Maintenance contracts provide operating services for existing government-owned waste facilities, offering lowest-risk private sector entry requiring minimal capital investment while delivering operational expertise, efficiency improvements, and professional management. Under O&M arrangements, government retains facility ownership and major capital expenditure responsibilities while contracting private operator to manage daily operations, perform routine and preventive maintenance, employ and supervise workforce, procure consumables and spare parts, comply with environmental regulations, and achieve specified performance targets. Contract duration typically spans 3-7 years balancing government flexibility to change operators against private party need for sufficient term recovering mobilization costs and demonstrating performance improvements justifying contract renewal or extension.

O&M contracts suit existing waste facilities underperforming due to inadequate management, technical deficiencies, or operational inefficiencies where professional private sector management can achieve substantial improvements without major capital investment. Common applications include sanitary landfills requiring improved operations including cell management, leachate treatment, gas collection, environmental monitoring, and public health protection; material recovery facilities needing optimized sorting operations, equipment maintenance, and market development for recovered materials; composting facilities requiring process control, quality management, and product marketing; and transfer stations benefiting from logistics optimization and equipment maintenance improving efficiency. Investment requirements remain minimal, typically covering working capital for payroll, consumables, and spare parts inventory rather than facility improvements which remain government responsibility unless contract specifically provides otherwise.

O&M Contract Elements:

Scope of Services:

• Daily operations: Staffing, shift management, waste receipt and processing

• Preventive maintenance: Scheduled servicing per manufacturer recommendations

• Corrective maintenance: Repairs of breakdowns, component replacements (minor)

• Housekeeping: Cleanliness, order, general appearance of facilities

• Record-keeping: Operations logs, maintenance records, incident reports

• Regulatory compliance: Permit conditions, environmental monitoring, reporting

Government Retained Responsibilities:

• Facility ownership: Legal title, property taxes, insurance

• Major capital repairs: Structural improvements, equipment replacement

• Capacity expansions: Additional cells, new equipment, facility extensions

• Regulatory approvals: Permit renewals, environmental compliance liabilities

• Policy decisions: Service scope, hours, acceptance criteria

• Financial risk: Revenue shortfalls, demand variations

Performance Standards and Monitoring:

• Operational metrics: Throughput, processing efficiency, recovery rates

• Environmental compliance: Emissions, effluents, residues meeting permit limits

• Equipment availability: Uptime targets, maintenance completion rates

• Safety performance: Accident rates, lost-time incidents, near-misses

• Customer service: Complaint resolution, stakeholder satisfaction

• Financial management: Budget compliance, cost controls, reporting

Compensation and Incentives:

• Fixed monthly fee: Covering staffing, routine maintenance, consumables

• Variable component: Based on throughput or processing volumes

• Performance bonuses: For exceeding targets or achieving excellence

• Performance penalties: Deductions for failures, non-compliance, poor performance

• Cost savings sharing: Mechanisms rewarding efficiency improvements

• Pass-through costs: Utilities, waste disposal, extraordinary repairs

O&M contract success depends heavily on clear definition of responsibilities and performance expectations, avoiding ambiguity about which party bears costs for various maintenance, repairs, or improvements. Well-structured contracts establish baseline conditions through facility assessment before contract start, define normal wear versus extraordinary damage, specify cost responsibility thresholds distinguishing routine maintenance from major repairs, and provide mechanisms for contract adjustments if facility conditions or service requirements change substantially during contract term. Performance monitoring through regular inspections, data review, and stakeholder feedback enables early identification of performance issues requiring corrective action while documentation supports objective evaluation of operator performance at contract renewal time. Indonesian local governments increasingly utilize O&M contracts for waste facilities as cost-effective approach accessing private sector expertise while maintaining public ownership consistent with political and policy preferences.

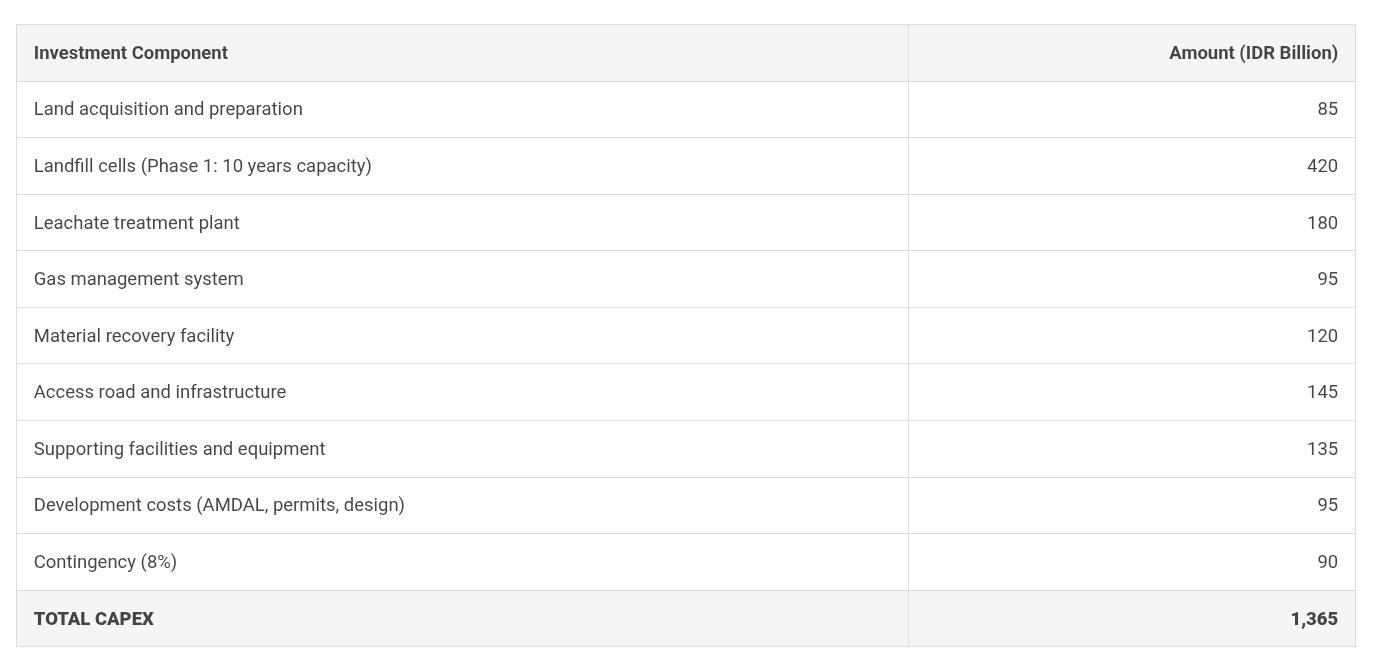

Case Study: Regional Sanitary Landfill BOT Project

Project Overview:

Location: Regional cooperation serving 3 kabupaten, Central Java

Scope: Integrated sanitary landfill with material recovery and leachate treatment

Design Capacity: 500 tons per day (current), expandable to 800 TPD

Land Area: 25 hectares including buffer zones

Catchment Population: 1.2 million people across three jurisdictions

Contract Structure: BOT with 25-year concession period

Partnership Model: Special Purpose Vehicle with local and international partners

Technical Components:

Landfill Cells: Engineered cells with composite liner (HDPE + clay), gas collection

Leachate Treatment: Aerobic-anaerobic biological treatment, meeting Permen LHK standards

Gas Management: Collection system for methane capture and flaring

MRF Component: Basic sorting for recyclables recovery before landfilling

Weighbridge: Automated system tracking incoming waste volumes

Access Road: 8 km dedicated access from main highway

Supporting Facilities: Workshop, administration, environmental monitoring equipment

Financial Structure:

Financing Structure:

• Equity: IDR 410 billion (30% - SPV shareholders)

• Senior Debt: IDR 820 billion (60% - Infrastructure fund + commercial bank)

• Viability Gap Fund: IDR 135 billion (10% - Ministry of Finance KPBU support)

Revenue Model and Cash Flow:

Tipping Fee Structure:

• Base tipping fee: IDR 135,000/ton (Year 1, escalates 4% annually)

• Minimum volume guarantee: 400 TPD (80% of design capacity)

• Payment responsibility: Three participating kabupaten pro-rata by waste volume

Annual Operating Costs (Steady State):

• Personnel (42 staff): IDR 8.4 billion/year

• Leachate treatment operations: IDR 12.5 billion/year

• Equipment maintenance and fuel: IDR 9.8 billion/year

• Environmental monitoring: IDR 3.2 billion/year

• Insurance and administration: IDR 4.1 billion/year

Total OPEX: IDR 38 billion/year

Additional Revenue Streams:

• Recyclables sales: IDR 4.5 billion/year (15% processing efficiency)

• Compost sales (organic fraction): IDR 2.8 billion/year

Financial Performance Metrics:

Project IRR (Equity): 14.2% over 25-year concession

Net Present Value: IDR 287 billion (@ 10% discount rate)

Debt Service Coverage Ratio: 1.35 (minimum 1.20 required by lenders)

Payback Period: 12.5 years (discounted)

Government Cost per Ton: IDR 135,000 (Year 1) vs IDR 180,000 if developed publicly

Value for Money: 25% NPV savings vs Public Sector Comparator

✅ Project Status: Operational Success

Project commissioned 2021, currently processing 480 TPD with excellent environmental compliance. Regional cooperation model successfully distributes costs across jurisdictions. Tipping fees remain 30% below alternatives while meeting all performance standards. Financial close achieved through blended financing structure combining equity, commercial debt, and government VGF support demonstrating KPBU viability for waste infrastructure.

Waste-as-a-Service (WaaS) Business Model

Waste-as-a-Service represents emerging partnership model where comprehensive waste management solutions are provided under outcomes-based pricing structures, with service providers owning infrastructure and bearing operational risks while customers pay predictable fees for defined service levels. WaaS model originated in commercial and industrial sectors where businesses seek to outsource non-core waste management functions while ensuring regulatory compliance, cost predictability, and sustainability performance. Service scope typically encompasses collection equipment and logistics, sorting and processing infrastructure, treatment and disposal arrangements, regulatory compliance management, reporting and documentation, and continuous improvement programs optimizing waste reduction, reuse, and recycling outcomes. Unlike traditional transactional waste services charging per pickup or per ton, WaaS pricing based on comprehensive service packages incentivizing providers to maximize waste diversion, resource recovery, and operational efficiency.

WaaS applications prove particularly suitable for industrial parks providing centralized waste management services to multiple tenants, large commercial complexes including shopping malls and office towers generating diverse waste streams, hotel and resort operations requiring reliable service meeting environmental commitments, hospital and healthcare facilities managing medical and general waste under strict regulations, and institutional customers including universities, government facilities, and large corporations prioritizing sustainability while focusing on core missions rather than waste management complexities. Service providers invest in collection equipment, sorting facilities, processing technologies, and disposal access while leveraging economies of scale across multiple customers, specialized expertise optimizing operations, and capital availability financing infrastructure individual customers cannot justify independently.

WaaS Model Characteristics:

Service Scope and Responsibilities:

• Waste collection: Containers, trucks, collection routes, scheduling

• On-site management: Staff, equipment, monitoring, housekeeping

• Sorting and processing: Material recovery, composting, residue management

• Treatment and disposal: Arrangements with licensed facilities

• Regulatory compliance: Permits, manifests, reporting, audits

• Sustainability reporting: Diversion rates, GHG emissions, circular economy metrics

Pricing Structure Options:

• Fixed monthly fee: Predictable cost based on facility size, waste generation estimates

• Per-unit pricing: Cost per ton or cubic meter with minimum commitments

• Performance-based: Base fee plus incentives for diversion rate improvements

• Gain-sharing: Savings from waste reduction or material revenues shared

• Bundled services: Comprehensive package including equipment, operations, disposal

• Multi-year contracts: 5-10 year terms with annual escalation provisions

Service Level Agreements:

• Collection frequency: Daily, multiple times daily, or on-call service

• Response times: Maximum time for service calls, equipment issues

• Diversion targets: Recycling and composting rate goals

• Contamination limits: Maximum acceptable levels in recyclable streams

• Regulatory compliance: 100% compliance with all applicable regulations

• Reporting frequency: Monthly performance dashboards, quarterly reviews

Value Proposition for Customers:

• Operational simplicity: Single point of contact, comprehensive solution

• Cost predictability: Fixed or predictable pricing vs variable waste costs

• Regulatory compliance: Expert management reduces compliance risk

• Sustainability performance: Improved diversion rates, ESG reporting

• Capital avoidance: No investment in waste equipment or infrastructure

• Focus on core business: Outsource non-core waste management function

WaaS providers differentiate through service quality, technology capabilities, sustainability performance, and customer relationship management rather than competing primarily on price. Successful operators deploy digital platforms enabling real-time monitoring of collection activities, contamination tracking supporting customer education, performance dashboards visualizing diversion rates and trends, and data analytics identifying optimization opportunities. Technology investments including IoT-enabled containers with fill-level sensors, route optimization software, automated sorting equipment, and blockchain-based material tracking create competitive advantages while improving operational efficiency. Customer retention depends heavily on service reliability, responsive account management, transparent reporting, and demonstrated sustainability improvements supporting customers' environmental commitments and stakeholder communications.

Comprehensive Partnership Scheme Selection Framework

Selecting optimal partnership structure requires systematic evaluation across multiple dimensions including project characteristics, financial considerations, risk allocation preferences, institutional capacity, and strategic objectives. No single partnership model proves universally superior; rather, appropriateness depends on specific context with different schemes offering advantages and disadvantages relative to particular circumstances. Decision framework should examine project scale and complexity, with major infrastructure warranting long-term concessions like BOT or DBFOM while smaller facilities may suit DBO or O&M contracts; available financing, distinguishing government-financed projects enabling DBO from those requiring private capital through BOT/BOO/DBFOM structures; risk tolerance, with risk-averse governments preferring O&M or DBO limiting private sector control while those seeking maximum risk transfer favor BOO or DBFOM; institutional capacity, where capable agencies can manage DBO or O&M contracts while those with limited expertise benefit from comprehensive BOT or WaaS arrangements; and strategic priorities, including desires for eventual asset ownership favoring BOT over BOO, or sustainability focus suggesting performance-based WaaS models.

Financial analysis proves essential for partnership selection, comparing total lifecycle costs across alternative delivery models accounting for upfront capital requirements, annual operating payments, performance incentives and penalties, risk mitigation costs, and transaction expenses. Public Sector Comparator (PSC) methodology estimates costs if government develops and operates project independently, providing baseline for evaluating private sector proposals and determining value for money from partnership approaches. Well-structured PSC incorporates realistic cost estimates avoiding optimism bias, appropriate risk adjustments reflecting actual government experience with comparable projects, and lifecycle perspective capturing operations, maintenance, and renewal costs over extended periods rather than focusing only on initial capital costs. Value for Money assessment compares PSC against partnership proposals on net present value basis, with positive differences indicating partnerships deliver better value while negative differences suggest direct government provision would cost less, though qualitative factors including risk transfer, service quality, and innovation may justify partnerships even when quantitative VfM appears marginal.

Partnership Model Selection Decision Tree

Scenario 1: Large-Scale New Infrastructure (500+ TPD)

IF: Government lacks capital but has revenue/payment capacity

THEN: Consider BOT or DBFOM

Rationale: Private financing addresses capital constraints, long concession enables cost recovery, eventual transfer provides public ownership

Requirements: Creditworthy government, adequate tariffs or budget, clear demand projections, VGF if needed

Scenario 2: Specialized Treatment Facility

IF: B3 hazardous waste, medical waste, or industrial treatment serving commercial customers

THEN: Consider BOO or WaaS

Rationale: Commercial customers accept service fees, specialized technology requires private expertise, no public ownership need

Requirements: Sufficient customer base, regulatory framework for private ownership, competitive positioning

Scenario 3: Medium-Scale Facility with Government Funding

IF: Capital available (IDR 50-500B) but limited technical capacity or desire for performance accountability

THEN: Consider DBO

Rationale: Integrated delivery reduces interface risks, operations phase ensures design quality, government retains ownership

Requirements: Available budget, clear performance specifications, monitoring capacity, realistic schedule

Scenario 4: Existing Underperforming Facility

IF: Facility exists but performs poorly due to management/technical deficiencies

THEN: Consider O&M Contract

Rationale: Low-risk improvement option, private expertise addresses operational issues, government retains assets

Requirements: Baseline assessment, clear responsibilities, performance metrics, adequate compensation

Scenario 5: Industrial Park or Commercial Complex

IF: Multiple tenants/occupants requiring comprehensive integrated waste services

THEN: Consider Waste-as-a-Service

Rationale: Centralized service achieves economies, sustainability performance, tenants prefer operational simplicity

Requirements: Adequate waste volumes, long-term occupancy, willingness to pay service fees, sustainability focus

Scenario 6: Regional Mega-Project (1000+ TPD)

IF: Multi-jurisdictional project serving large population requiring sophisticated technology

THEN: Consider DBFOM with Government Guarantees

Rationale: Scale justifies complexity, private lifecycle responsibility, government support mitigates risks enabling financing

Requirements: Inter-governmental agreement, robust feasibility study, VGF/guarantees, experienced transaction advisor

Risk allocation represents critical partnership structuring consideration, with optimal arrangements assigning each risk to party best able to manage it at lowest cost rather than attempting maximum risk transfer regardless of consequences. Construction risk naturally rests with private sector given their control over design, procurement, and execution, while demand risk may be shared through minimum guarantees (public) and marketing efforts (private) rather than fully transferring to either party. Technology risk requires careful assessment distinguishing proven technologies with performance records enabling private sector assumption from novel or unproven approaches where shared risk or government backing proves necessary. Regulatory and policy risks generally remain with government given their control over these factors and inability of private parties to mitigate through own actions, though contracts should address how policy changes affecting economics will be handled avoiding either party bearing unfair burden from uncontrollable external changes. Financial modeling should quantify risk impacts through probability-weighted scenarios, determining which party can bear risks at lowest cost to project and structuring allocation accordingly.

Regulatory Framework and Procurement Processes

Indonesian waste management partnerships operate within comprehensive regulatory framework established through multiple laws and implementing regulations. UU No. 18/2008 on Waste Management provides foundational legislation establishing waste management principles, institutional responsibilities, private sector participation provisions, and regulatory oversight mechanisms.1 Presidential Regulation No. 38/2015 on KPBU (Government and Business Entity Cooperation) establishes detailed framework for public-private partnerships across infrastructure sectors including waste management, defining permissible partnership structures, procurement procedures, risk allocation principles, government support mechanisms including viability gap funding and guarantees, and monitoring and evaluation requirements.2 Ministry of Finance regulations issued by KPBU unit provide operational guidance on project preparation, transaction management, and financial support application procedures supporting local governments developing bankable partnership projects.

KPBU procurement follows structured process beginning with project identification and preliminary assessment determining partnership suitability, progressing through detailed feasibility study examining technical, financial, legal, and environmental aspects, then business case development including Public Sector Comparator establishing value for money baseline. Government completes project preparation culminating in final business case and tender documents before proceeding to competitive procurement typically following two-stage process with initial prequalification selecting shortlist of qualified bidders based on experience, technical capability, and financial capacity, followed by detailed proposal submission where shortlisted bidders submit technical and financial proposals evaluated against predetermined criteria weighted toward lifecycle value rather than merely lowest price. Preferred bidder selection leads to negotiation finalizing contract terms, financial arrangements, and government support provisions before financial close when all conditions precedent are satisfied and construction can commence.

KPBU Procurement Process Timeline:

Phase 1 - Project Preparation (12-18 months):

• Project identification and screening (2-3 months)

• Feasibility study: technical, financial, legal, environmental (6-9 months)

• Business case development including PSC (2-3 months)

• AMDAL and permitting (concurrent with feasibility)

• Budget allocation and approval process (3-4 months)

• Transaction advisor procurement if external support needed

Phase 2 - Procurement (8-12 months):

• Tender document preparation (2-3 months)

• Market sounding and pre-qualification (2-3 months)

• Request for Proposal to shortlisted bidders (3-4 months)

• Proposal evaluation and preferred bidder selection (2-3 months)

• Contract negotiation (concurrent with evaluation)

• Approvals: APBN/APBD, ministry endorsement, DPRD if required

Phase 3 - Financial Close (4-8 months):

• Financing arrangement finalization (3-6 months)

• Government support documentation (VGF, guarantees)

• Conditions precedent satisfaction (land, permits, approvals)

• SPV establishment and equity funding

• Contract signing and financial close

• Mobilization and construction commencement

Total Timeline: 24-38 months from initiation to construction start

Government support mechanisms prove critical for marginal waste projects where user fees or budget allocations alone cannot provide adequate returns attracting private investment. Viability Gap Funding (VGF) provides capital grant up to maximum 49% of project value filling gap between commercially viable return threshold and returns achievable from available revenue streams, with Ministry of Finance administering central VGF facility while sector ministries and local governments may provide additional support. Government guarantees cover specific risks including demand shortfalls through minimum volume commitments, regulatory changes affecting project economics, and currency or interest rate risks for projects with foreign investment or financing. Land provision eliminates acquisition risk and costs, often proving decisive for project viability given Indonesia's complex land ownership and acquisition processes. Availability or shadow tolls provide revenue certainty through government payments based on facility availability meeting performance standards rather than actual usage, particularly valuable for projects with uncertain demand or where user fees prove politically or practically difficult to implement.

Frequently Asked Questions About Waste Management Partnership Schemes

1. What are the main differences between BOT and BOO partnership models for waste infrastructure?

BOT (Build-Operate-Transfer) involves private party financing, constructing, and operating waste facility for 20-30 year concession period before transferring ownership to government, suitable when government desires eventual asset ownership for long-term public service provision. BOO (Build-Own-Operate) provides permanent private ownership with indefinite operating rights under service agreements, appropriate for specialized facilities serving commercial customers or when government prefers avoiding future asset management responsibilities. BOT requires transfer planning and asset condition specifications, while BOO provides greater private sector flexibility for facility evolution and technology upgrades throughout extended ownership period. Indonesian applications include BOT for regional landfills and municipal waste facilities where public ownership aligns with service universality objectives, versus BOO for B3 hazardous waste treatment and industrial waste services where commercial dynamics and specialized expertise support permanent private ownership.

2. How long does KPBU procurement typically take for waste management projects in Indonesia?

Complete KPBU process from project identification to financial close typically requires 24-38 months comprising project preparation phase (12-18 months) including feasibility studies, business case, and tender documentation; procurement phase (8-12 months) covering prequalification, bidding, evaluation, and preferred bidder selection; and financial close phase (4-8 months) finalizing financing arrangements, satisfying conditions precedent, and completing contract execution. Timeline variations depend on project complexity, land acquisition requirements, permit approvals, political considerations, and financing arrangements with international lenders requiring longer due diligence. Indonesian government through Ministry of Finance KPBU unit provides project preparation facilities and transaction advisory support potentially reducing timelines through professional project structuring, though realistic planning should accommodate 2.5-3 year periods from conception to construction commencement for major waste infrastructure partnerships.

3. What government support mechanisms are available for waste management KPBU projects?

Indonesian government provides multiple support mechanisms improving waste KPBU project viability including Viability Gap Funding (VGF) offering capital grants up to 49% of project value filling gaps between commercial viability thresholds and achievable returns; government guarantees covering demand risk through minimum volume commitments, regulatory change impacts, and currency/interest rate risks; land provision eliminating acquisition costs and risks; availability payments providing revenue certainty through government payments based on facility performance rather than usage; and tax incentives including VAT exemptions, import duty waivers for equipment, and accelerated depreciation reducing tax burdens. Ministry of Finance administers central VGF facility, while PT SMI (Sarana Multi Infrastruktur) provides project preparation financing and advisory services, and PT PII (Penjaminan Infrastruktur Indonesia) issues infrastructure guarantees mitigating political and regulatory risks for qualified projects meeting viability and public interest criteria.

4. Is Waste-as-a-Service model viable for municipal solid waste or only commercial/industrial applications?

Waste-as-a-Service currently proves most viable for commercial and industrial applications including industrial parks, commercial complexes, hotels, hospitals, and large institutions where customers possess willingness and ability to pay service fees covering comprehensive waste management solutions. Municipal solid waste presents challenges for pure WaaS model due to difficulty charging residential users adequate fees, political sensitivity of waste charges, and universal service obligations requiring coverage of non-paying or economically marginal areas. However, hybrid models emerge combining WaaS principles with government contracts, such as municipalities contracting private operators providing comprehensive waste management services for defined geographic areas under performance-based agreements, essentially functioning as municipal WaaS though structured as service contracts rather than direct user fees. Future municipal applications may expand as regulatory frameworks evolve supporting outcomes-based contracting, digital platforms enable granular service tracking, and sustainability priorities justify premium pricing for comprehensive waste management delivering environmental performance exceeding basic collection and disposal.

5. What typical returns can private investors expect from waste management partnerships in Indonesia?

Expected returns vary substantially by partnership structure, waste segment, and risk profile with equity IRR typically ranging 12-18% for large-scale BOT/DBFOM infrastructure projects with government counterparties and moderate risk allocation, 15-22% for BOO facilities serving commercial customers with market risk and permanent ownership, 10-15% for DBO contracts with government financing and limited private capital at risk, and 18-25% for specialized services including B3 hazardous waste treatment reflecting higher technical requirements and regulatory risks. Returns depend heavily on revenue certainty through minimum volume guarantees or take-or-pay obligations, tariff levels and escalation provisions, government creditworthiness and payment reliability, regulatory stability, and financing costs with local currency debt commanding 9-12% interest rates while foreign currency financing may offer lower rates offset by currency risk. Well-structured projects with appropriate risk allocation, government support through VGF or guarantees, and proven technology typically achieve lower-middle range returns, while projects with greater uncertainty, limited government support, or novel approaches require higher returns compensating increased risk.

6. How are tipping fees or gate fees typically structured in waste facility BOT contracts?

Tipping fee structures in BOT waste facilities typically comprise base fee per ton covering operating costs, debt service, equity returns, and contingencies; automatic escalation provisions adjusting annually for inflation (typically 3-5%), fuel cost variations affecting collection and equipment operations, and currency fluctuations if foreign financing involved; minimum volume guarantees where government commits delivering minimum waste quantities (typically 70-80% of design capacity) with payments due regardless of actual deliveries protecting revenue downside; excess volume provisions addressing deliveries exceeding guaranteed minimums, often at reduced marginal rates since fixed costs already covered; and periodic true-up mechanisms adjusting fees if actual costs, volumes, or other factors vary significantly from projections. Example structure: base tipping fee IDR 150,000/ton in year 1 escalating 4% annually, minimum guarantee 400 TPD with government paying for shortfalls, marginal rate IDR 100,000/ton for volumes exceeding 500 TPD, five-year true-up reviewing cost variations exceeding ±15% triggering fee renegotiation. Fee levels must balance financial viability for private operator against affordability for government and competitiveness with alternative disposal options.

7. What are the key risks for private companies entering Indonesian waste management sector?

Major risks include demand uncertainty from waste generation varying with economic activity, informal sector competition, and waste diversion programs reducing volumes available for contracted facilities; regulatory risks including permit delays, environmental standard changes, policy shifts affecting waste management approaches, and political interference in operations or fee-setting; payment risks particularly with local government counterparties having limited fiscal capacity, budget constraints, or political transitions disrupting payment commitments; land acquisition delays and community opposition causing project delays and cost overruns; technology risks if novel or unproven systems underperform guarantees; environmental liability from historical contamination, operational upsets, or long-term impacts; and market risks for facilities generating revenues from recyclable commodity sales facing price volatility. Risk mitigation requires thorough due diligence assessing government creditworthiness, realistic demand projections avoiding optimism bias, proven technology selection, robust contracts with minimum volume guarantees and payment security mechanisms, adequate insurance, strong community engagement, and contingency reserves for uncertainties. Most successful partnerships feature careful risk allocation placing risks with parties best able to manage them rather than attempting full risk transfer to private sector.

8. Can small-to-medium local companies participate in KPBU waste projects or are they limited to large corporations?

While major KPBU projects typically attract large corporations or consortia given substantial capital requirements, technical complexity, and financing capacity needs, smaller waste projects and various partnership roles enable local company participation. Local firms can serve as consortium members bringing regional knowledge, community relationships, and operational capabilities partnering with larger companies providing financing and technical expertise; subcontractors for construction, equipment supply, or specialized services during project development and operations; operations contractors under DBO or O&M arrangements requiring expertise but limited capital; or lead developers for smaller-scale projects including TPS3R facilities, material recovery operations, or specialized waste services where capital requirements and complexity remain within local company capacity. Government procurement may include local content requirements, SME participation targets, or evaluation criteria favoring local partnerships encouraging local company involvement. Capacity building initiatives from government agencies, development banks, and industry associations provide training, financing access, and technical support helping local companies develop capabilities for waste sector participation, though realistic assessment of technical and financial requirements remains essential ensuring commitments can be fulfilled.

9. How do waste management partnerships address informal sector workers currently providing collection and recycling services?

Informal sector integration proves critical for waste partnership success and social acceptance given thousands of waste pickers, collectors, and recyclers deriving livelihoods from existing systems. Best practice partnerships incorporate informal sector through structured arrangements including contracted collection services where informal collectors formalize as small enterprises contracting with facility operators; employment opportunities at facilities for sorting, processing, or other activities suitable for former informal workers; dedicated recyclable material supply arrangements where informal collectors deliver materials to facilities at specified quality and pricing; training and capacity building supporting informal sector upgrade to formal micro-enterprises meeting business registration, safety, and quality standards; and stakeholder engagement ensuring informal sector voices are heard during project planning and transition periods. Several successful Indonesian projects established cooperative structures or associations representing informal workers, negotiated transition periods allowing gradual formalization, provided equipment and training supporting professionalization, and designed facilities accommodating informal sector participation in material recovery value chains. Social impact assessments during project preparation should quantify informal sector livelihoods affected and develop comprehensive transition plans ensuring workers' concerns addressed through inclusive rather than displacement approaches.

10. What performance metrics and KPIs should be included in waste management partnership contracts?

Comprehensive waste facility contracts should specify quantifiable performance indicators including service availability measuring percentage of time facility operates meeting specifications (typically 90-95% target with penalties for shortfalls); throughput capacity demonstrating ability to process contracted waste volumes at design specifications; environmental compliance tracking emissions, effluents, and residues against permit limits with zero tolerance for violations; resource recovery efficiency measuring diversion of recyclables, compost, and energy recovery as percentage of incoming waste; safety performance including lost-time accident rates, worker safety incidents, and vehicle accident frequencies; customer service metrics for collection operations including complaint resolution times and service delivery reliability; and financial performance comparing actual costs against budgets and fee structures. Contracts should establish baseline measurements, monitoring and reporting frequencies (typically monthly operations reports plus quarterly detailed reviews), independent verification procedures, and consequences for performance variations including payment adjustments, remediation requirements, and termination rights for persistent failures. Performance incentives rewarding superior performance often prove more effective than penalties alone, creating positive motivation for continuous improvement. Monitoring systems increasingly utilize digital platforms with real-time data collection through sensors, GPS tracking, and automated reporting enabling proactive management rather than reactive problem response.

Strategic Recommendations and Future Outlook

Indonesian waste management sector presents substantial business opportunities across diverse partnership structures serving municipal solid waste, commercial and industrial waste, hazardous waste, and specialized streams. Companies evaluating market entry or expansion should conduct comprehensive assessment of target segments, partnership models, regional priorities, competitive landscape, and required capabilities informing strategic positioning. Municipal solid waste management remains dominated by government provision though KPBU frameworks increasingly enable private participation in major infrastructure including regional landfills, material recovery facilities, and emerging waste-to-energy projects requiring substantial capital and technical capabilities. Commercial and industrial segments offer more immediate opportunities through service contracts, Waste-as-a-Service arrangements, and facility operations requiring moderate investment while leveraging operational expertise and customer relationship management.

Partnership model selection should reflect project characteristics, financial structures, risk allocation, and institutional context rather than assuming universal superiority of any single approach. Large-scale infrastructure warranting BOT or DBFOM arrangements requires patient capital, risk management capabilities, and government relationship building navigating complex procurement processes spanning several years from conception to operation. DBO offers integrated delivery for government-financed projects emphasizing performance accountability and lifecycle optimization. O&M contracts provide low-risk entry leveraging operational expertise for existing facilities. BOO models suit specialized services serving commercial customers where permanent private ownership aligns with market dynamics. Emerging WaaS approaches create opportunities in industrial parks, commercial complexes, and institutional customers prioritizing comprehensive sustainability solutions.

Successful waste management partnerships require capabilities spanning technical expertise in appropriate technologies and environmental management, financial strength or access supporting capital requirements and working capital needs, operational excellence delivering reliable service meeting performance commitments, stakeholder management including government relationships and community engagement, regulatory compliance ensuring permitting and ongoing operations meet evolving requirements, and commercial acumen developing viable business models and competitive positioning. Companies lacking certain capabilities should consider partnerships, consortia arrangements, or phased development strategies building capacity progressively rather than overcommitting to projects beyond current capabilities risking performance failures damaging reputation and future opportunities.

Looking forward, Indonesian waste sector evolution toward circular economy principles, resource recovery emphasis, and climate change mitigation creates opportunities for innovative business models and technologies. Waste-to-energy including modern combustion, gasification, and anaerobic digestion technologies gains policy support as renewable energy source addressing both waste management and energy security objectives. Material recovery facilities incorporating advanced sorting technologies, artificial intelligence, and robotics improve economics of recyclable material recovery. Organic waste processing through composting and anaerobic digestion serves both waste management and sustainable agriculture markets. B3 hazardous waste treatment infrastructure remains critically undersupplied relative to industrial generation requiring specialized facilities. Digital technologies enabling smart waste management through IoT sensors, data analytics, and platform business models create differentiation opportunities. Companies positioning at intersection of waste management, circular economy, renewable energy, and digital transformation technologies can capture emerging opportunities while contributing to sustainable development objectives aligning business success with environmental and social benefits.

International Frameworks for Waste Management Business Models

Download these authoritative international references providing comprehensive frameworks for waste management partnership schemes and business models:

1. Integrated Solid Waste Management Framework (UNEP, 2011)

Comprehensive ISWM planning methodology covering stakeholder roles, public-private partnership models, technology selection criteria, financing mechanisms, and global best practices for sustainable waste management system development applicable across diverse contexts.

2. What a Waste: Global Review of Solid Waste Management (World Bank, 2012)

Authoritative global assessment documenting waste management systems worldwide, financing approaches, institutional arrangements, private sector participation models, cost structures, and comparative analysis of urban waste systems providing benchmarking data for investment planning.

3. Waste Management and Circular Economy in OECD Countries (OECD, 2019)

Comprehensive policy analysis examining legal frameworks, remediation strategies, circular economy transition approaches, extended producer responsibility schemes, and comparative assessment of waste management systems across OECD member countries with actionable recommendations.

4. ISWM Concept and Technology Selection (RWM Global, 2020)

Technical annex detailing integrated sustainable waste management systems, waste hierarchy implementation, technology assessment criteria, lifecycle cost analysis methodologies, and decision frameworks for selecting appropriate treatment and disposal technologies matching local conditions.

5. Zero Waste Global Strategies (UNDP, 2025)

Contemporary strategies for waste reduction through behavioral change, multi-stakeholder partnerships, circular economy business models, and integrated approaches combining prevention, reuse, recycling, and recovery maximizing resource efficiency while minimizing environmental impacts.

6. Waste Lifecycle and Circular Economy Overview (UNOSD, 2023)

Comprehensive overview of waste management lifecycle approach incorporating EU Waste Framework Directive principles, circular economy action plans, resource efficiency strategies, and sustainable development goal alignment for integrated system design and implementation.

7. Integrated Waste Management Assessment Framework (IRC, 2023)

Assessment and planning framework linking water-sanitation-waste management sectors, stakeholder engagement methodologies, institutional capacity evaluation, financing strategy development, and monitoring frameworks supporting integrated infrastructure planning.

8. Airport Waste Management Guidelines (ICAO, 2018)

International Civil Aviation Organization guidelines for specialized waste handling at airports including infectious waste, catering waste, hazardous materials, and operational waste streams with regulatory compliance requirements, contractor management, and environmental protection protocols.

9. E-Waste Management Framework (DCO, 2025)

International collaboration framework for electronic waste management covering collection systems, dismantling and recovery technologies, hazardous material handling, circular economy integration, extended producer responsibility implementation, and sustainability metrics for e-waste value chains.

10. Lean Analysis Framework for Waste Optimization (JOSI, 2021)

International case study applying lean management principles to waste operations, efficiency optimization methodologies, process improvement techniques, cost reduction strategies, and performance measurement systems supporting continuous improvement in waste management service delivery.

Indonesian Frameworks and Policy Documents

Essential Indonesian government and institutional references providing regulatory frameworks, KPBU guidelines, and implementation cases for waste management business development:

1. Kajian Kebijakan Strategi Nasional Percepatan Pengelolaan Persampahan (Ekonomi Kreatif, 2023)

Comprehensive policy evaluation and strategic recommendations for accelerating national waste management covering regulatory frameworks, institutional strengthening, financing mechanisms, technology adoption, and KSNP-SPP (National Strategic Plan) implementation roadmap.

2. Outline Business Case Pengelolaan Sampah Manggar, Balikpapan (Bappenas/Balikpapan, 2023)

Detailed KPBU business case for municipal waste management including VfM (Value for Money) analysis, RDF/SRF (Refuse-Derived Fuel) technology assessment, financial modeling, risk allocation matrix, stakeholder roles per Bappenas regulations, and procurement strategy.

3. Peta Jalan Pengelolaan Sampah 2025 DKI Jakarta (WWF Indonesia, 2024)

Strategic roadmap for Jakarta waste management transformation toward circular economy model incorporating 3R principles, TPS3R/TPST optimization, multi-stakeholder collaboration including CSR partnerships, technology integration, and ambitious waste reduction targets through 2025.

4. Pengelolaan Sampah Berbasis Ekonomi Sirkular (KPBU Kemenkeu, 2024)

Ministry of Finance KPBU unit study examining circular economy-based waste management models, Balikpapan case analysis, public opinion assessment, business model frameworks, and policy implications for expanding private sector participation through structured partnerships.

5. Buku Bunga Rampai Pengelolaan Sampah (DPR RI Pusaka, 2022)

Parliamentary research compilation evaluating waste management policies, implementation challenges, 3R business model analysis, regulatory framework effectiveness, and comprehensive recommendations for improving national waste management system covering legislation, financing, and institutional coordination.

6. Pengelolaan Limbah Sido Muncul - Green Industry (PT Sido Muncul, 2024)

Corporate case study documenting industrial waste management best practices including B3 hazardous waste TPS (temporary storage), IPAL (wastewater treatment) optimization, circular economy implementation, third-party contractor cooperation models, and sustainability performance metrics.

7. Logical Framework Approach dalam Pengelolaan Sampah (IPDN, 2023)

Academic analysis applying logical framework methodology to waste management partnerships, CSR collaboration models, 3R program implementation, TPS3R facility development, substantive regulatory analysis, and stakeholder coordination mechanisms supporting effective project design and execution.

8. Buku Pengendalian dan Pengelolaan Limbah Industri (USAHID, 2024)

Comprehensive industrial waste management textbook covering waste control frameworks, reduction strategies, reclamation technologies, regulatory compliance requirements, B3 hazardous waste handling, treatment technologies, and business model frameworks for industrial waste service providers.

9. Model Pengelolaan Sampah Elektronik Berkelanjutan Jakarta (IPB, 2022)

Research thesis developing sustainable household e-waste management models for DKI Jakarta incorporating collection logistics, sorting and dismantling operations, recycling value chains, stakeholder participation, and policy recommendations for scaling informal sector integration.

10. Strategi Pengelolaan Sampah Berkelanjutan (Neliti, 2023)

Academic journal article examining sustainable waste management strategies for Indonesian cities, integrated system approaches, community participation mechanisms, technology adoption challenges, financing constraints, and institutional capacity building requirements for improved service delivery.

References and Data Sources:

1. DPR RI Pusaka. (2022). Buku Bunga Rampai Pengelolaan Sampah: Kebijakan, Implementasi, dan Inovasi.

https://berkas.dpr.go.id/pusaka/files/buku_bunga_rampai/buku-bunga-rampai-public-5.pdf

2. Kementerian Keuangan - KPBU. (2024). Pengelolaan Sampah Berbasis Ekonomi Sirkular dan Implikasinya bagi Indonesia.

https://kpbu.kemenkeu.go.id/read/1220-1758/umum/kajian-opini-publik/pengelolaan-sampah-berbasis-ekonomi-sirkular-dan-implikasinya-bagi-indonesia

3. Bappenas / Pemerintah Kota Balikpapan. (2023). Outline Business Case untuk Pengelolaan Sampah Manggar.

https://web.balikpapan.go.id/uploaded/PS_Executive_Summary.pdf

4. WWF Indonesia. (2024). Peta Jalan (Roadmap) Pengelolaan Sampah 2025 DKI Jakarta.

https://plasticsmartcities.wwf.id/storage/user_uploads/a3a837eab802ef5bbf9472a94c98183c.pdf

5. Kementerian Koordinator Bidang Perekonomian. (2023). Kajian Kebijakan dan Strategi Nasional Percepatan Pengelolaan Persampahan.

https://www.ekon.go.id/source/publikasi/Kajian%20Kebijakan%20dan%20Strategi%20Nasional%20Percepatan%20Pengelolaan%20Persampahan.pdf

6. United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). (2011). Integrated Solid Waste Management Framework.

https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/dsd/csd/csd_pdfs/csd-19/learningcentre/presentations/May%202%20am/1%20-%20Memon%20-%20ISWM.pdf

7. The World Bank. (2012). What a Waste: A Global Review of Solid Waste Management.

https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/302341468126264791/pdf/68135-REVISED-What-a-Waste-2012-Final-updated.pdf

8. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2019). Waste Management and the Circular Economy in Selected OECD Countries.

https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2019/09/waste-management-and-the-circular-economy-in-selected-oecd-countries_g1g99aca/9789264309395-en.pdf

9. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2025). Zero Waste Offer: Global Strategies for Waste Reduction.

https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2025-08/zero_waste_offer.pdf

10. UN Office for Sustainable Development (UNOSD). (2023). Brief Overview of Waste Management: Life-cycle Approach Towards the Circularity.

https://unosd.un.org/sites/unosd.un.org/files/session_v._introductory_session_mr._park_brief_overview_of_waste_management_lifecycle_approach_towards_the_circularity.pdf

11. IRC WASH. (2023). Integrated Waste Management Assessment and Planning Framework.

https://www.ircwash.org/sites/default/files/irc_integrated_waste_management_assessment_and_planning_framework_2023_01.pdf

12. International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). (2018). Waste Management at Airports.

https://www.icao.int/sites/default/files/sp-files/environmental-protection/Documents/Waste_Management_at_Airports_booklet.pdf

13. Development Cooperation Organization (DCO). (2025). E-Waste Management Framework.

https://dco.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/DCO-E-Waste-Management-Framework.pdf

14. PT Sido Muncul Tbk. (2024). Pengelolaan Limbah Menuju Green Industry.

https://investor.sidomuncul.co.id/newsroom/Pengelolaan-Limbah.pdf

15. Institut Pemerintahan Dalam Negeri (IPDN). (2023). Logical Framework Approach dalam Pengelolaan Sampah.

http://eprints.ipdn.ac.id/17004/1/Arda%20Geby%20Ayu%20Salsa_31.0254_D4%20FIX.pdf

16. Universitas Sahid Jakarta. (2024). Buku Pengendalian dan Pengelolaan Limbah Industri.

http://repository.usahid.ac.id/4159/1/Buku%20ISBN%20Pengendalian%20dan%20Pengelolaan%20Limbah%20Industri%20(1).pdf

17. Institut Pertanian Bogor (IPB). (2022). Model Pengelolaan Sampah Elektronik Berkelanjutan untuk Rumah Tangga di DKI Jakarta.

https://repository.ipb.ac.id/jspui/bitstream/123456789/157916/1/cover_P0602201010_3812d34411a247aaa16d03b20bc9658e.pdf

18. Neliti. (2023). Strategi Pengelolaan Sampah Berkelanjutan.

https://media.neliti.com/media/publications/278832-strategi-pengelolaan-sampah-berkelanjuta-9ff90f8c.pdf

19. RWM Global. (2020). ISWM Concept: Sustainable Systems and Technology Selection.

https://rwm.global/utilities/SPG-Start/SPG/Annexes/US%20Sizes/Annex%204B.3.pdf

20. Jurnal Optimasi Sistem Industri (JOSI). (2021). Lean Analysis Framework for Waste Management.

https://josi.ft.unand.ac.id/index.php/josi/article/view/141

Professional Waste Management Partnership Advisory Services

SUPRA International provides comprehensive consulting services for waste management partnership development including business model assessment and selection, feasibility studies for BOT/BOO/DBO/WaaS schemes, KPBU project structuring and procurement support, financial modeling and risk analysis, regulatory compliance and permitting assistance, technology evaluation and vendor selection, stakeholder engagement strategies, and transaction advisory through financial close. Our expertise serves government agencies developing waste infrastructure partnerships, private sector companies evaluating market entry or expansion opportunities, and industrial customers seeking comprehensive waste management solutions optimizing environmental performance and lifecycle costs.

Services encompass partnership scheme comparison and selection frameworks, Public Sector Comparator development, Value for Money analysis, contract structuring and risk allocation design, government support mechanism optimization, environmental and social impact assessment, informal sector integration planning, and performance monitoring system design ensuring sustainable waste management outcomes through appropriate partnership structures matching project characteristics, institutional contexts, and strategic objectives.

Developing waste management partnerships or evaluating waste infrastructure investment opportunities?

Contact us to discuss partnership structuring, feasibility assessment, and transaction advisory services

Share:

If you face challenges in water, waste, or energy, whether it is system reliability, regulatory compliance, efficiency, or cost control, SUPRA is here to support you. When you connect with us, our experts will have a detailed discussion to understand your specific needs and determine which phase of the full-lifecycle delivery model fits your project best.