How Carbon Capture and Storage Works: A Clear, Structured Explanation of Indonesia’s Carbon Capture and Storage Pathways

Carbon Capture and Storage in Indonesia: Technology, Regulatory Frameworks, Projects, Business Models, and Regional Leadership Opportunities in Asia-Pacific CCS Development

Reading Time: 58 minutes

Key Highlights

• Storage capacity potential: Indonesia possesses estimated 400-600 gigatons of geological CO₂ storage capacity in depleted oil and gas reservoirs and deep saline aquifers, positioning nation as potential Asia-Pacific regional hub serving high-emission economies including Singapore, Japan, and South Korea requiring cross-border carbon storage solutions lacking domestic geological formations

• Regulatory framework advancement: Government established comprehensive legal structure through MEMR Regulation 2/2023 governing CCS in upstream oil and gas, Presidential Regulation 14/2024 providing umbrella framework, and MEMR Regulation 16/2024 enabling non-PSC contractors operate designated carbon storage permit areas, with provisions allowing 30% storage capacity allocation for international CO₂ imports

• Major project development: Pertamina advances CCS hubs in Asri Basin (partnering ExxonMobil and Korea's KNOC with 1.1-3.0 gigatons capacity requiring USD 2 billion investment), Kutai Basin, and Offshore North West Java, while bp develops Tangguh CCUS project (25-30 million tons capacity over 10-15 years expected onstream 2028) and 15+ projects targeted operations by 2030

• Business model innovation: Emerging revenue streams include carbon credit monetization, CO₂ storage services for domestic and international emitters, enhanced oil recovery integration generating 30-40% production increases, and blue hydrogen/ammonia production enablement, with government incentives including cost recovery treatment, fiscal incentives, and public-private partnership frameworks supporting commercial viability

Executive Summary

Carbon capture and storage represents technological pathway enabling continued operation of fossil fuel-based energy infrastructure and hard-to-abate industrial facilities while substantially reducing greenhouse gas emissions through capturing carbon dioxide at source before atmospheric release, transporting captured CO₂ to suitable geological formations, and permanently storing underground in depleted hydrocarbon reservoirs or deep saline aquifers. Indonesia recognizes CCS as integral component of national climate strategy targeting net-zero emissions by 2060, with 29% reduction by 2030, leveraging vast geological storage potential estimated between 400-600 gigatons, equivalent to centuries of regional industrial emissions, combined with extensive existing oil and gas infrastructure facilitating cost-effective deployment and strategic geographic position serving Southeast Asian and Northeast Asian high-emission economies requiring carbon storage solutions.

International Energy Agency identifies CCUS technologies as necessary pillar achieving global net-zero targets, with cumulative 107 gigatons CO₂ requiring permanent storage through 2060 under Clean Technology Scenario, while operational capacity globally reaches only 50 million tons annually as of first quarter 2025 despite accelerating project announcements representing USD 27+ billion investment commitments. Indonesia positions itself capturing substantial share of emerging global CCS market through aggressive regulatory development, strategic international partnerships, and coordinated project deployment across multiple geological basins spanning Sumatra, Java, Kalimantan, and Papua. Government commitment demonstrated through comprehensive legal framework establishment, international engagement with Singapore, South Korea, and Japan regarding cross-border CO₂ transport and storage, and active promotion of 19 oil and gas blocks conversion to carbon storage facilities engaging multinational energy majors including ExxonMobil, bp, INPEX, Repsol, and domestic champion Pertamina.

Technology applications span capture from natural gas processing facilities (currently representing 65% global operational capacity given low capture costs), power generation enabling continued coal and gas plant operation, industrial emissions from cement, steel, and chemical production representing hard-to-abate sectors lacking viable alternatives, and atmospheric carbon dioxide removal through direct air capture or bioenergy with CCS supporting negative emissions requirements. Transport infrastructure utilizes pipelines (potentially repurposing existing oil and gas networks reducing costs 90% versus new construction), specialized CO₂ carrier vessels for offshore storage sites, and integrated hub-and-spoke systems serving multiple emitters through shared infrastructure reducing individual project costs. Storage security depends on careful geological site selection ensuring caprock integrity, comprehensive monitoring systems detecting potential leakage, and regulatory frameworks establishing long-term liability transfer mechanisms protecting operators from perpetual stewardship obligations.

Business models supporting commercial viability include enhanced oil recovery generating revenue through incremental production (Pertamina trials demonstrating 30-40% increases), carbon credit monetization under compliance markets and voluntary schemes, storage-as-a-service for third-party emitters (particularly international sources), blue hydrogen production enabling decarbonized energy carriers, and government incentives including capital subsidies, operational cost recovery, tax credits, and guaranteed offtake agreements mitigating demand uncertainty. Economic analysis indicates capture costs ranging USD 30-100 per ton for natural gas processing to USD 50-150 for power generation and USD 80-200 for industrial applications depending on CO₂ concentration and scale, while transport costs span USD 2-14 per ton via pipeline and storage costs typically below USD 10 per ton for suitable formations, though combined systems require carbon pricing mechanisms or direct subsidies achieving competitiveness against unabated emissions alternatives.

Indonesia's CCS development strategy emphasizes five priority areas: comprehensive regulatory framework providing legal certainty and operational guidance, geological mapping and site characterization identifying optimal storage locations and quantifying capacity, international partnerships enabling cross-border CO₂ value chains and foreign investment attraction, technology development and deployment through pilot projects building domestic capability, and business model innovation ensuring commercial sustainability. Strategic positioning as regional CCS hub creates substantial economic opportunities including direct project investment (infrastructure, equipment, services), operational employment, technology transfer and capacity building, regional service export potential, and enhanced energy security supporting continued hydrocarbon resource utilization while meeting climate commitments. Successful implementation depends on sustained policy support, coordinated public-private collaboration, technical capacity development, and stakeholder acceptance addressing environmental concerns and community engagement ensuring social license enabling transformative infrastructure deployment across Indonesian archipelago.

Carbon Capture and Storage Technology Fundamentals

Carbon capture and storage encompasses three distinct phases: capture of CO₂ from emission sources or directly from atmosphere, transport to storage locations, and permanent geological storage preventing atmospheric release. Each phase presents distinct technical challenges, cost structures, and operational requirements demanding integrated system design optimizing total value chain economics rather than individual component optimization. Successful CCS deployment requires careful matching of capture technology with emission source characteristics, transport infrastructure appropriate to volumes and distances, and storage sites offering adequate capacity, security, and accessibility supporting decades-long injection operations and perpetual storage integrity.

Capture technologies separate CO₂ from gas streams through chemical, physical, or membrane processes with selection dependent on source concentration, pressure, temperature, and presence of other components. Pre-combustion capture extracts CO₂ before fuel burning through gasification producing hydrogen and CO₂ streams, enabling cleaner fuel utilization though requiring substantial infrastructure modifications unsuitable for existing facilities. Post-combustion capture treats flue gases after combustion through chemical absorption using amine solvents (most mature technology deployed in natural gas processing and fertilizer production), physical absorption for high-pressure streams, or membrane separation showing promise for lower costs though requiring additional development. Oxy-fuel combustion burns fuel in pure oxygen rather than air producing concentrated CO₂ streams simplifying capture though requiring energy-intensive oxygen production limiting current applications.

Carbon Capture Technology Overview:

Post-Combustion Capture:

• Chemical absorption: Amine-based solvents (MEA, DEA, MDEA) capturing CO₂ from flue gas at atmospheric pressure

• Typical conditions: 3-15% CO₂ concentration, 40-60°C temperature, atmospheric pressure

• Energy requirement: 2.5-4.0 GJ/ton CO₂ for regeneration primarily as low-pressure steam

• Capture efficiency: 85-95% depending on solvent selection and process configuration

• Applications: Coal and gas power plants, cement kilns, steel blast furnaces

• Cost range: USD 50-100/ton CO₂ for power generation, USD 80-150/ton for industrial sources

• Advantages: Retrofittable to existing facilities, mature technology with operating experience

• Limitations: High energy penalty (20-30% power output reduction), solvent degradation, space requirements

Pre-Combustion Capture:

• Gasification: Fuel conversion to synthesis gas (H₂ + CO) followed by water-gas shift reaction producing H₂ and CO₂

• Physical absorption: Selexol or Rectisol processes separating CO₂ at elevated pressure (typically 30-70 bar)

• Energy requirement: 1.5-2.5 GJ/ton CO₂ benefiting from high-pressure separation

• Capture efficiency: 90-98% given high CO₂ concentrations (15-40%) and pressure

• Applications: IGCC power plants, hydrogen production, synthetic fuel manufacturing

• Cost range: USD 40-80/ton CO₂ depending on scale and integration

• Advantages: Lower energy penalty, high-purity CO₂ stream, hydrogen co-production

• Limitations: Requires gasification infrastructure unsuitable for existing facilities, high capital cost

Oxy-Fuel Combustion:

• Process: Combustion in high-purity oxygen (>95% O₂) producing flue gas with 80-98% CO₂

• Oxygen production: Cryogenic air separation requiring 200-250 kWh/ton O₂

• Energy requirement: 2.0-3.5 GJ/ton CO₂ including oxygen production and compression

• Capture efficiency: 95-99% given inherently high CO₂ concentrations

• Applications: Purpose-built power plants, cement kilns, industrial boilers

• Cost range: USD 45-90/ton CO₂ depending on oxygen production efficiency

• Advantages: High-purity CO₂, elimination of NOₓ formation, existing boiler compatibility

• Limitations: Oxygen production energy penalty, flue gas recycle requirements, limited retrofitting potential

Direct Air Capture:

• Technology: Atmospheric CO₂ extraction using liquid solvents or solid sorbents

• Concentration challenge: 420 ppm CO₂ in air versus 3-15% in flue gas requiring massive throughput

• Energy requirement: 5-10 GJ/ton CO₂ given dilute source and regeneration demands

• Capture rate: Typically 0.5-2 tons CO₂ per day per unit in current pilot facilities

• Applications: Negative emissions, carbon removal offsetting unavoidable emissions

• Cost range: USD 200-600/ton CO₂ currently, targeting USD 100-200 with scale and optimization

• Advantages: Location-independent, addresses distributed emissions, permanent removal enabling negative emissions

• Limitations: Very high costs currently, energy-intensive, requires renewable energy avoiding emissions shifting

Transport infrastructure moves captured CO₂ from sources to storage sites utilizing pipelines for large volumes and continuous operations, shipping for offshore destinations or intermittent flows, and potentially rail or truck for small-scale or temporary applications though economically limited. Pipeline transport dominates current systems given lowest costs at scale, with over 8,000 kilometers operating globally (primarily United States for enhanced oil recovery) demonstrating technical feasibility and safety. CO₂ requires compression to 100-150 bar for pipeline transport maintaining dense phase (600-900 kg/m³) reducing volume and enabling efficient transmission, with compression representing 60-70% of transport costs. Pipeline construction costs range USD 50,000-150,000 per kilometer depending on diameter (typically 300-600 mm), terrain, population density affecting routing, and regulatory requirements, with operational costs including pumping energy, monitoring, and maintenance adding USD 2-5 per ton per 100 kilometers.

Shipping enables long-distance transport or service to offshore storage lacking pipeline infrastructure, with specialized carriers transporting liquid CO₂ at -50°C and 7 bar or intermediate temperature/pressure conditions (typically -30°C and 15 bar) balancing energy requirements against cargo capacity. Current commercial CO₂ shipping limited to food-grade applications transporting approximately 1,000 tons annually in Europe, though substantial interest developing regional CCS hubs in Asia requiring marine transport given archipelagic geography. Shipping costs vary dramatically with distance and volume, ranging USD 10-30 per ton for short distances (under 500 km) to USD 30-80 per ton for regional transport (1,000-3,000 km), becoming competitive with pipelines for offshore destinations or intermittent flows insufficient justifying dedicated pipeline infrastructure. Indonesia's geographic context favoring hub-and-spoke systems combining pipeline gathering networks concentrating captured CO₂ at coastal terminals, marine transport to offshore storage sites, and international imports utilizing existing shipping infrastructure developed for LNG and petroleum products.

Geological Storage: Site Selection, Capacity, and Security

Permanent CO₂ storage requires suitable geological formations providing adequate capacity, structural or stratigraphic trapping mechanisms preventing migration, and caprock seals ensuring long-term containment measured in millennia rather than decades. Primary storage options include depleted oil and gas reservoirs offering proven sealing capability demonstrated through hydrocarbon retention over geological timeframes, deep saline aquifers providing enormous potential capacity though requiring more extensive characterization given limited historical data, and unmineable coal seams offering potential CO₂ adsorption and methane displacement though capacity and operational uncertainties limiting current applications. Indonesia's geological endowment across multiple sedimentary basins including Central Sumatra, South Sumatra, East Java, Kutai, and offshore Northwest Java provides estimated 400-600 gigatons storage capacity substantially exceeding domestic requirements enabling regional hub development serving neighboring countries.

Depleted hydrocarbon reservoirs constitute most attractive initial storage targets given extensive characterization data from production operations, proven caprock integrity demonstrated through millions of years hydrocarbon retention, existing infrastructure potentially reducing development costs, and operators possessing geological expertise and regulatory relationships facilitating permitting. Indonesian oil and gas fields produced since 1970s offer substantial depleted capacity with government identifying 19 blocks for potential CCS conversion engaging operators including ExxonMobil, bp, INPEX, Repsol, and Pertamina. Storage capacity in depleted reservoirs depends on original hydrocarbon volume, recovery factor, and CO₂ density at reservoir conditions, with rough approximation of 0.5-0.8 tons CO₂ per barrel original oil in place or 0.9-1.1 tons per thousand cubic feet original gas, though detailed reservoir simulation required for accurate assessment given pressure, temperature, and formation heterogeneity influences.

Geological Storage Options and Characteristics:

Depleted Oil and Gas Reservoirs:

• Storage mechanism: Structural trapping in proven hydrocarbon-bearing formations

• Capacity estimation: 0.5-0.8 tons CO₂ per barrel original oil, 0.9-1.1 tons per Mcf original gas

• Depth requirements: Typically 800-3,000 meters ensuring supercritical CO₂ conditions (>31°C, >74 bar)

• Advantages: Proven sealing, extensive characterization data, existing infrastructure, operational familiarity

• Challenges: Residual hydrocarbons, abandoned well integrity, limited capacity compared to saline aquifers

• Enhanced oil recovery potential: CO₂-EOR generating revenue offsetting storage costs

• Examples in Indonesia: Jatibarang field (CO₂-EOR trial 30-40% increase), Sukowati field, planned Asri Basin development

Deep Saline Aquifers:

• Storage mechanism: Stratigraphic trapping in porous sandstone sealed by impermeable shale or mudstone

• Capacity estimation: 1-4% pore volume convertible to CO₂ storage (efficiency factor varying with geology)

• Global capacity: Estimated 10,000+ gigatons potentially available worldwide

• Indonesia capacity: 400-600 gigatons across multiple sedimentary basins

• Advantages: Enormous capacity, widespread distribution, no hydrocarbon production conflicts

• Challenges: Limited characterization requiring exploration drilling, caprock integrity assessment, pressure management

• Key formations: Upper Talang Akar (Asri Basin), Balikpapan sandstone (Kutai), Attaka West sandstone (ONWJ)

• Monitoring requirements: Seismic surveys, pressure monitoring, geochemical sampling verifying containment

Site Selection Criteria:

• Capacity: Minimum 50-100 million tons for commercial-scale projects supporting 20-30 year operations

• Injectivity: Permeability >50-100 millidarcies enabling economic injection rates

• Seal integrity: Thick (>20 meters) low-permeability caprock with no faults penetrating seal

• Depth: 800-3,000 meters optimal range balancing supercritical conditions against drilling costs

• Proximity: Within 50-300 kilometers major emission sources minimizing transport costs

• Accessibility: Onshore or shallow offshore (<500 meters water depth) for cost-effective development

• Regulatory: Permitted zones, no conflicts with mineral rights or protected areas

• Infrastructure: Existing facilities, pipelines, or proximity to transport networks reducing capital requirements

Storage Security and Monitoring:

• Containment mechanisms: Structural trapping (immediate), residual trapping (10-100 years), solubility trapping (100-1,000 years), mineral trapping (1,000+ years)

• Leakage risks: Abandoned well integrity (primary risk), caprock fracturing, fault reactivation

• Monitoring techniques: 3D/4D seismic imaging plume migration, downhole pressure and temperature, geochemical sampling, surface monitoring (soil gas, groundwater)

• Regulatory requirements: Monitoring/reporting/verification (MRV) protocols, baseline characterization, operational monitoring, post-closure surveillance

• Closure criteria: Plume stability demonstration, pressure dissipation, no detectable leakage

• Long-term stewardship: Indonesia PR 14/2024 requires 10-year post-closure monitoring before liability transfer to government

• International standards: ISO 27914, London Protocol amendments, national storage regulations

Injection operations require careful pressure management preventing formation fracturing or inducing seismicity, with injection rates constrained by formation permeability, well count, and acceptable pressure increases. Supercritical CO₂ (existing at reservoir conditions exceeding 31°C and 74 bar) behaves as dense fluid (600-800 kg/m³) providing favorable storage density while maintaining sufficient mobility for injection. Wells utilize similar technology to oil and gas production with modifications including corrosion-resistant materials (given CO₂ acidity in presence of water), specialized cements ensuring long-term integrity, and rigorous quality control given perpetual containment requirements. Multiple injection wells typically required for commercial-scale projects, with 30-50 million ton capacity requiring 5-10 wells depending on reservoir characteristics and injection duration spreading capital costs over extended operations.

Long-term monitoring verifies storage security through multiple surveillance techniques tracking injected CO₂ plume migration, formation pressure responses, potential leakage pathways, and groundwater quality surrounding storage complex. Time-lapse (4D) seismic surveys repeated at 1-5 year intervals image subsurface CO₂ distribution demonstrating containment within target formations, though resolution limits requiring supplementary techniques for comprehensive surveillance. Downhole monitoring using permanently installed sensors provides continuous pressure, temperature, and geochemical data at injection intervals and overlying formations enabling early leak detection. Surface monitoring including atmospheric measurements, soil gas sampling, and groundwater chemistry establishes baseline conditions before injection and detects any surface expression of potential leakage events, though natural CO₂ variability requiring sophisticated statistical methods distinguishing operational impacts from background fluctuations. Indonesia's regulatory framework under PR 14/2024 requires operators fund monitoring activities continuing 10 years post-closure before liability transfer to government, creating long-term financial obligations requiring consideration in project economics.

Indonesia's Regulatory Framework for CCS Development

Indonesian government established comprehensive legal foundation for CCS development through three-tier regulatory hierarchy providing umbrella policy framework, sector-specific implementation rules, and operational guidelines enabling both upstream oil and gas contractors and independent entities engage carbon storage activities. Presidential Regulation 14/2024 enacted January 30, 2024, establishes broad national policy framework defining CCS activities, organizational structures, licensing mechanisms, operational requirements, and cross-border provisions, serving as foundation for subordinate ministerial regulations addressing technical details. This represents strategic government commitment positioning Indonesia as regional CCS leader through proactive policy development ahead of most Southeast Asian nations lacking comparable legal clarity, attracting international investment and partnership opportunities requiring regulatory certainty before committing substantial capital.

Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources Regulation 2/2023 issued March 3, 2023, provides detailed framework for CCS and CCUS implementation within upstream oil and gas working areas operated under production sharing contracts (PSCs), enabling contractors utilize existing geological understanding, infrastructure, and regulatory relationships facilitating rapid deployment. Regulation distinguishes CCS (permanent storage reducing emissions) from CCUS (utilizing captured CO₂ in industrial processes or enhanced oil recovery before storage), establishing specific requirements for each including development planning, environmental assessment, operational procedures, monitoring obligations, and decommissioning provisions. Contractors receive operational cost recovery for CCS activities under PSC terms, creating favorable economics compared to purely commercial ventures bearing full capital and operational expenses without cost recovery mechanisms, though revenue allocation and fiscal treatment requiring careful negotiation balancing contractor returns against government take.

Indonesia CCS Regulatory Framework Summary:

Presidential Regulation 14/2024 (Enacted January 30, 2024):

• Scope: Umbrella framework for all CCS activities across Indonesia

• Organizational authority: Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (MEMR) primary regulator

• Implementation pathways: (1) PSC contractors in oil and gas working areas, (2) Independent entities in designated carbon storage permit areas (WIPK)

• Licensing process: Exploration permits converting to storage operation permits following site characterization

• Cross-border provisions: Permits CO₂ imports up to 30% storage capacity enabling regional hub development

• Long-term liability: Operators responsible for 10-year post-closure monitoring before government assumption

• International engagement: Framework supporting bilateral agreements (Indonesia-Singapore CCS partnership)

• Subordinate regulations: Directs MEMR issue detailed technical and fiscal implementation rules

MEMR Regulation 2/2023 (Issued March 3, 2023):

• Scope: CCS and CCUS in upstream oil and gas working areas under PSCs

• Applicable contractors: Entities with PSCs under SKK Migas or BPMA (Aceh) supervision

• Development planning: Contractors propose CCS/CCUS as part of field development plans requiring MEMR/SKK Migas approval

• Cost recovery: CCS operational costs recoverable under PSC terms for CO₂ from upstream sources

• Technical requirements: Engineering standards, procurement procedures, construction oversight, operational protocols

• Monitoring obligations: Periodic reporting, measurement systems, emergency response capabilities

• Monetization options: Carbon trading, storage service fees, cost reimbursement for shared facilities

• Work area relinquishment: Contractors may return depleted CCS sites to government before PSC expiration

MEMR Regulation 16/2024 (Effective December 24, 2024):

• Scope: Carbon storage in designated permit areas (WIPK) outside existing oil and gas working areas

• Eligible entities: Indonesian incorporated companies or permanent establishments

• WIPK designation: MEMR determines permit areas through geological assessment or entity proposal

• Licensing sequence: (1) Exploration permit for site characterization, (2) Storage operation permit following successful exploration

• Tender process: Open tender for MEMR-identified areas, direct selection for entity-proposed sites

• Exploration commitments: Bidders propose exploration work programs evaluated in tender selection

• Storage agreements: Detailed contracts specifying injection rates, capacity allocation, fees, and operational terms

• Asset ownership: Equipment purchased by storage operators remains private property (versus state assets under PSCs)

Supporting Regulations and Guidelines:

• SKK Migas PTK-070/2024: Technical guideline implementing MEMR 2/2023 for PSC contractors

• Law 7/2021: Taxation Harmonization Law providing potential carbon tax reductions for CCS activities

• Carbon trading regulations: Framework enabling CCS projects generate and monetize carbon credits

• Environmental regulations: AMDAL (EIA) requirements, monitoring standards, reporting obligations

• International agreements: Bilateral frameworks with Singapore, MoUs with South Korea and Japan

• Fiscal incentives: Tax holidays, accelerated depreciation, import duty exemptions for CCS equipment

• Forthcoming regulations: MEMR developing detailed rules on certification processes, fee calculation methodologies, safety standards

MEMR Regulation 16/2024 effective December 24, 2024, complements PSC-based regime by enabling carbon storage in designated permit areas (Wilayah Izin Penyimpanan Karbon or WIPK) awarded through competitive tender or direct selection to Indonesian companies or permanent establishments, expanding CCS development beyond oil and gas operators to specialized storage providers, power generators, industrial emitters, and international entities establishing local operations. WIPK licensing follows two-stage process: exploration permits enabling geological characterization, test drilling, and capacity assessment followed by storage operation permits authorizing commercial-scale injection and long-term monitoring. Tender evaluation emphasizes exploration work commitments rather than revenue bids, incentivizing thorough site characterization building confidence in storage security and capacity estimates supporting subsequent storage operations, with shortlisted qualified bidders receiving preferential treatment in subsequent tenders recognizing demonstrated technical and financial capabilities.

Cross-border CO₂ provisions under PR 14/2024 permit importing captured carbon from other countries up to 30% licensed storage capacity, establishing legal foundation for Indonesia serving regional hub role addressing neighboring nations' limited domestic geological storage. Singapore possesses virtually no suitable storage formations given small land area and shallow geology, Japan's onshore options limited despite offshore potential in Sea of Japan, while South Korea similarly constrained, creating substantial demand for international storage services if carbon pricing or regulations mandate industrial emissions reduction. Indonesia-Singapore bilateral framework under development following Letter of Intent signing aims establish legally binding agreement enabling CO₂ export from Singapore to Indonesian storage facilities, potentially generating substantial revenue through storage service fees while supporting Singapore's climate commitments requiring deep decarbonization despite geographic constraints. Similar discussions progressing with South Korea (KNOC participation in Asri Basin project) and Japan (collaboration on Tangguh and Gundih projects) indicate regional recognition of Indonesia's strategic position and geological advantages.

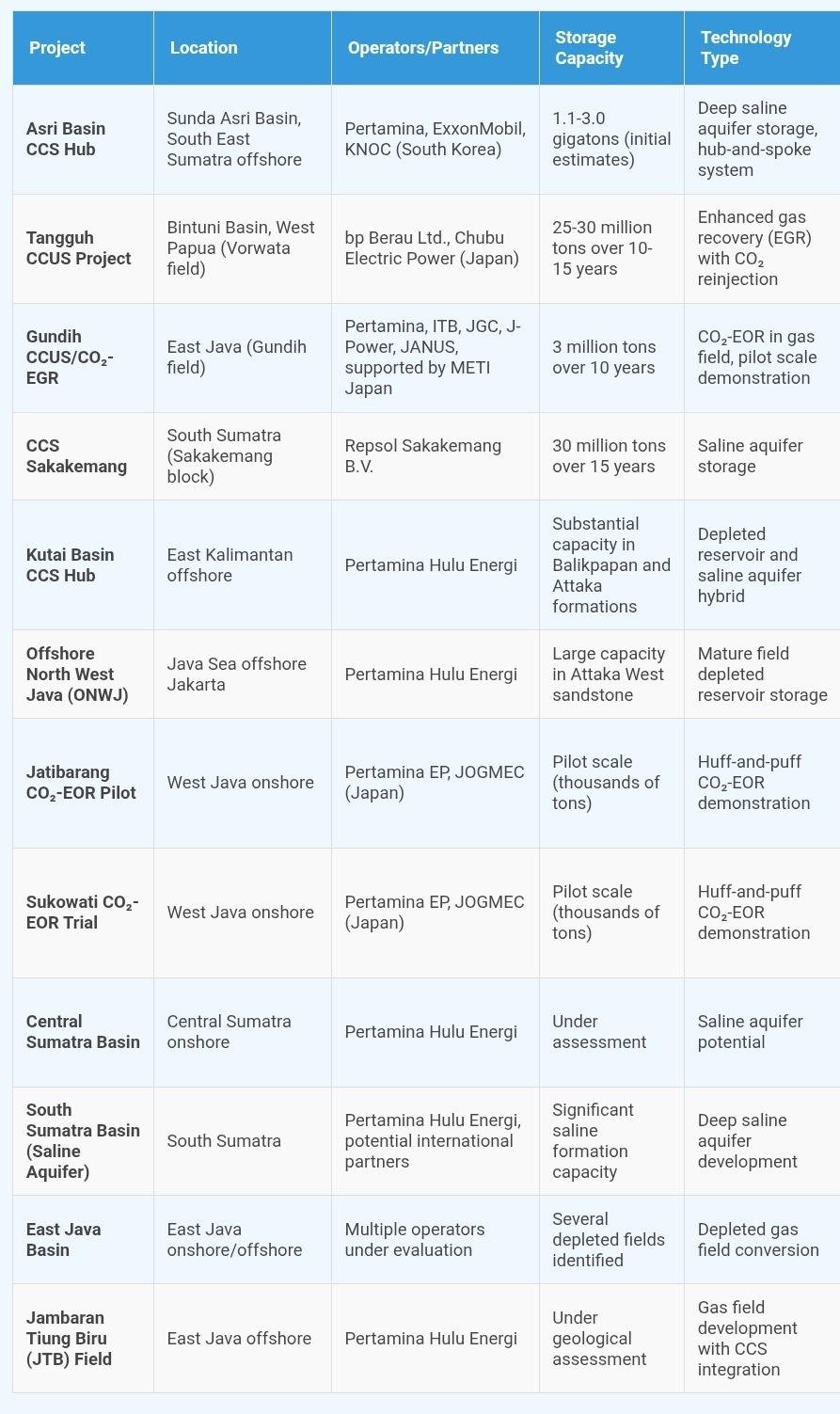

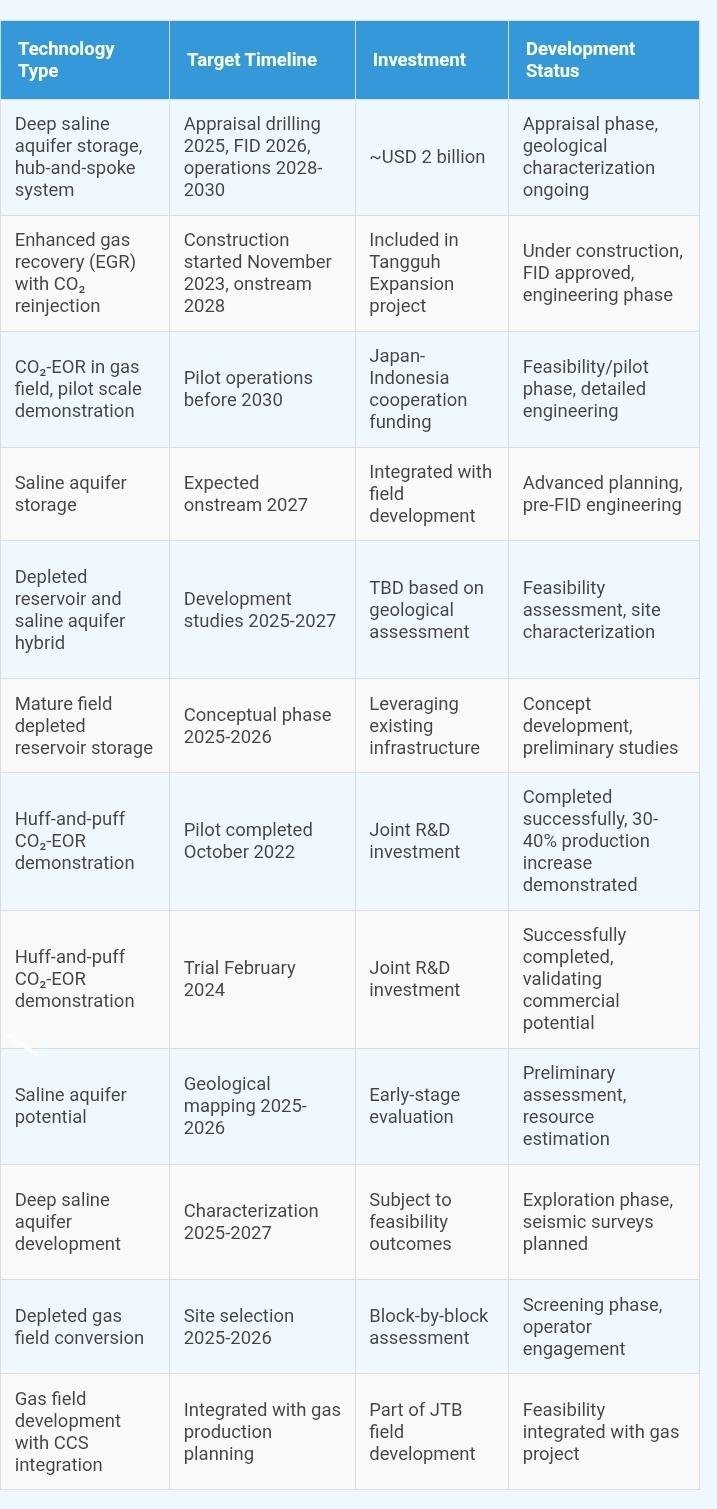

Major CCS Projects and Development Pipeline in Indonesia

Indonesia's CCS project pipeline encompasses 15-19 initiatives at various development stages from feasibility studies through engineering design to pilot operations, with government targeting commercial operations by 2028-2030 timeframe supporting national emissions reduction commitments. Projects span multiple geological basins leveraging depleted hydrocarbon reservoirs and deep saline aquifers, engage diverse technology applications including natural gas processing, enhanced oil recovery, power generation, and industrial emissions capture, and involve major international energy companies partnering with Indonesian entities bringing technology expertise, project finance capabilities, and global market connections accelerating deployment. Coordinated development across multiple projects creates ecosystem effects including shared infrastructure utilization, technology transfer, workforce development, regulatory learning, and investor confidence building driving successive project waves beyond initial pioneers.

Asri Basin CCS Hub represents flagship development partnership between Pertamina and ExxonMobil with Korean National Oil Corporation (KNOC) participation, targeting massive storage capacity estimated 1.1-3.0 gigatons in offshore Sunda Asri Basin located in Pertamina's South East Sumatra block. Partnership signed during 2024 Indonesian petroleum industry conference formalized collaboration conducting appraisal drilling assessing geological suitability through core sampling and comprehensive data gathering informing final investment decision anticipated 2025-2026. Project requires approximately USD 2 billion investment developing capture, transport, and injection infrastructure serving both domestic industrial emitters and international sources through cross-border CO₂ import provisions, positioning Asri as regional hub potentially accepting captured carbon from Singapore, Malaysia, and other Southeast Asian economies lacking domestic storage. ExxonMobil brings extensive global CCS experience including leading North America's largest CO₂ pipeline network and operating multiple enhanced oil recovery projects, while KNOC's participation enables South Korean industrial emissions diversion addressing domestic storage limitations and climate policy requirements mandating substantial emission reductions by 2030-2050.

Indonesia Major CCS Projects Overview

Pertamina Hulu Energi documented potential carbon storage capacity 7.3 gigatons across saline aquifers and depleted oil/gas fields in various regions, positioning state energy company as central player Indonesian CCS ecosystem through multiple hub-and-satellite development model. Strategy emphasizes creating regional CCS hubs at optimal geological locations (Asri Basin, Kutai Basin, ONWJ) equipped with major infrastructure supporting multiple injection sites, connected to satellite facilities at smaller storage locations through pipeline networks, and accessible to international emitters through marine CO₂ transport enabling cross-border business development. Hub approach reduces unit costs through infrastructure sharing, enables phased capacity additions responding to market demand growth, provides redundancy and flexibility accommodating different CO₂ sources and volumes, and creates network effects attracting additional emitters and service providers building integrated ecosystem.

Tangguh CCUS Project operated by bp in West Papua's Bintuni Basin represents most advanced Indonesian development with final investment decision approved, construction commenced November 2023, and operations targeted 2028 capturing CO₂ from natural gas processing and reinjecting into Vorwata gas field for enhanced gas recovery while permanently storing processed volumes. Project expects capture and store 25-30 million tons over 10-15 year operational period, with bp signing Memorandum of Understanding with Japan's Chubu Electric Power exploring CCS value chain connecting Japanese industrial emissions to Indonesian storage positioning Tangguh as potential international hub. Natural gas processing CCS offers lowest capture costs (USD 30-60 per ton) given high CO₂ concentrations (2-15%) in raw gas streams requiring separation anyway for LNG specifications, making early projects economically viable without substantial subsidies required for power generation or industrial capture facing higher costs and lower CO₂ concentrations.

Business Models and Revenue Streams for CCS Operations

Commercially viable CCS deployment requires multiple revenue streams offsetting substantial capital investments (capture facilities, pipelines, injection wells, monitoring systems) and ongoing operational expenditures (energy consumption, maintenance, monitoring, regulatory compliance) given captured CO₂ possesses limited intrinsic value unlike extracted petroleum generating direct commodity sales. Primary business models emerging globally and applicable Indonesian context include enhanced oil or gas recovery where CO₂ injection increases hydrocarbon production generating revenue offsetting capture and storage costs, carbon credit monetization under compliance schemes or voluntary markets rewarding verified emissions reductions, storage-as-a-service charging third-party emitters (domestic or international) for permanent CO₂ disposal, government incentives including capital grants, operational subsidies, tax credits, and guaranteed offtake agreements, and industrial decarbonization enabling continued facility operation under emissions regulations mandating reductions otherwise forcing facility closure.

Enhanced oil recovery using CO₂ flooding represents most commercially proven CCS application globally with over 70 projects operating primarily in United States Permian Basin and decades operational experience demonstrating technical feasibility and economic returns. CO₂-EOR involves injecting compressed CO₂ into depleted oil reservoirs reducing oil viscosity, maintaining reservoir pressure, and mobilizing residual oil trapped after conventional production, potentially recovering additional 10-20% original oil in place while permanently storing 40-60% injected CO₂ in reservoir (remainder returns to surface with produced oil requiring separation and reinjection). Pertamina's pilot trials at Jatibarang (October 2022) and Sukowati (February 2024) fields in West Java conducted jointly with Japan's JOGMEC demonstrated 30-40% production increases validating commercial potential for Indonesian mature fields supporting continued oil revenue while providing CO₂ storage capacity and operational experience informing larger-scale deployment.

CCS Business Models and Revenue Sources:

Enhanced Oil/Gas Recovery (EOR/EGR):

• Mechanism: CO₂ injection improving hydrocarbon recovery from mature fields

• Revenue source: Incremental oil or gas production sold at market prices

• CO₂ storage efficiency: 40-60% injected CO₂ permanently retained in formation

• Production increase: Typically 10-20% original oil in place (OOIP), Pertamina trials showing 30-40%

• Economics: Self-financing when oil price >USD 50-70/barrel depending on CO₂ costs

• Advantages: Proven technology, direct revenue generation, no carbon price dependency

• Limitations: Requires suitable mature oil fields, partial CO₂ recycling, limited storage capacity

• Applications: Jatibarang and Sukowati pilots (Indonesia), Permian Basin (US), Weyburn project (Canada)

Carbon Credit Monetization:

• Compliance markets: EU ETS carbon prices €80-100 per ton, potential Indonesia carbon tax/trading system

• Voluntary markets: Carbon removal credits USD 50-200+ per ton depending on permanence and verification

• Methodology: ISO 27916 CCS quantification standards, CDM methodologies, national protocols

• Verification: Third-party validation, monitoring/reporting/verification (MRV) systems, registry enrollment

• Revenue timing: Annual credit issuance following verified storage, long-term monitoring obligations

• Market risks: Price volatility, regulatory changes, additionality demonstration requirements

• Indonesia framework: Carbon trading regulations under development, international market access potential

• Credit volume: 1 ton CO₂ permanently stored = 1 carbon credit (varies by protocol and permanence classification)

Storage-as-a-Service:

• Fee structure: Typically USD 30-80 per ton CO₂ depending on location, capacity, services included

• Customer segments: Domestic industrial emitters, international sources (Singapore, Japan, Korea)

• Services included: Injection, monitoring, regulatory compliance, liability assumption post-closure

• Contract terms: 10-25 year agreements matching emitter facility lifetimes

• Capacity allocation: Firm commitments versus interruptible service, take-or-pay versus actual usage

• Risk allocation: Operator bears geological risk, emitter retains emissions compliance obligations

• Cross-border premium: International storage may command 20-40% premium versus domestic given limited alternatives

• Indonesia advantage: 30% import capacity allowance, regional geological advantage, strategic location

Government Incentives and Support:

• Capital subsidies: Infrastructure development grants, equipment cost-sharing, exploration funding

• Operational support: Direct payments per ton stored (US 45Q tax credit USD 85/ton for permanent storage)

• Tax incentives: Corporate tax holidays, accelerated depreciation, import duty exemptions

• Cost recovery: Indonesia PSC contractors recover CCS operational costs reducing net investment

• Offtake agreements: Government guarantees purchasing carbon credits or storage capacity

• Regulatory streamlining: Expedited permitting, simplified approval processes, one-stop service

• Research funding: Pilot project support, demonstration grants, technology development programs

• International support: Multilateral development banks, bilateral climate finance, concessional lending

Storage-as-a-service model charges third-party emitters fees for permanent CO₂ disposal combining injection, monitoring, regulatory compliance, and long-term liability management into comprehensive service offering enabling emitters focus on core operations while outsourcing carbon management complexity. Fee structures typically range USD 30-80 per ton depending on location, storage site characteristics, services included, contract terms, and market competition, with international cross-border storage potentially commanding premium pricing given emitter nations' limited alternatives. Indonesia's strategic advantages including vast geological capacity, existing infrastructure, favorable regulatory framework allowing 30% international allocations, and lower operational costs compared to developed economies position competitive pricing attracting regional demand while generating attractive returns for storage operators justifying substantial capital investments. Pertamina International Shipping developing specialized LCO₂ (liquefied CO₂) carrier fleet and reception terminal capabilities supporting marine transport infrastructure essential enabling cross-border business serving Singapore, Japan, and Korea sources.

Government incentives prove determining factor CCS commercial viability given current absence meaningful carbon pricing in most jurisdictions and substantial upfront investments required without guaranteed revenue streams. United States' 45Q tax credit expanded 2018 provides USD 85 per ton captured and permanently stored (USD 60 per ton for EOR or alternative uses) for 12 years from project commencement, spurring dozens new project announcements representing billions dollars investment previously uneconomic. European Union Innovation Fund financed from ETS revenues allocates approximately USD 1.5 billion to CCUS projects supporting capital cost reduction, while national governments including Netherlands (USD 7.3 billion), Denmark (USD 1.2 billion), United Kingdom (multi-billion pound support for industrial clusters), and Norway (funding entire Longship project value chain) demonstrate commitment recognizing CCS necessity achieving climate targets. Indonesia developing comparable incentive frameworks including potential carbon tax reduction for CCS implementers, fiscal incentives under investment laws, and cost recovery provisions for PSC contractors reducing effective project costs.

Economic Analysis: Costs, Investments, and Financial Viability

Carbon capture and storage costs vary dramatically depending on CO₂ source concentration and capture technology, transport distance and mode, storage type and location, project scale enabling economies, and financing terms affecting capital recovery. Natural gas processing offers lowest capture costs USD 30-60 per ton given high CO₂ concentrations (2-15%) requiring separation anyway for pipeline or LNG specifications, utilizing physical or chemical absorption in large-scale facilities processing millions tons annually amortizing capital costs. Power generation faces higher costs USD 50-100 per ton for coal plants (10-15% CO₂ in flue gas) or USD 60-120 for gas plants (3-5% CO₂) due to lower concentrations, atmospheric pressure operation, and large volumes requiring massive equipment, while industrial sources including cement USD 80-150, steel USD 80-200, and chemicals USD 70-180 vary by process specifics and integration opportunities.

Transport costs depend primarily on distance, volume, and infrastructure availability with pipelines offering lowest unit costs at scale though requiring high upfront capital investment. New pipeline construction costs USD 50,000-150,000 per kilometer for typical 300-600 mm diameter depending on terrain, regulatory requirements, and population density affecting routing, with operational costs including compression energy (primary expense), monitoring, and maintenance adding USD 2-5 per ton per 100 kilometers. Existing oil and gas pipeline repurposing dramatically reduces costs to 10% new construction expense (approximately USD 5,000-15,000 per kilometer) assuming compatible materials and necessary modifications, creating substantial advantages in regions with extensive hydrocarbon infrastructure like Indonesia's mature producing basins. Marine transport via specialized CO₂ carriers becomes economical for distances exceeding 500-1,000 kilometers or offshore destinations lacking pipeline access, with costs ranging USD 10-30 per ton short distances (under 500 km) to USD 30-80 per ton regional scale (1,000-3,000 km) depending on vessel availability, loading/unloading infrastructure, and utilization rates.

CCS Cost Components and Ranges:

Capture Costs by Source Type:

• Natural gas processing: USD 30-60/ton (high concentration 2-15%, physical separation, mature technology)

• Ammonia/fertilizer production: USD 30-70/ton (high purity streams, straightforward capture)

• Coal-fired power (post-combustion): USD 50-100/ton (10-15% CO₂, chemical absorption, 20-30% energy penalty)

• Gas-fired power (post-combustion): USD 60-120/ton (3-5% CO₂, large volumes, lower concentration)

• Cement kilns: USD 80-150/ton (15-30% CO₂ but high temperature, particulates, integration complexity)

• Steel production (blast furnace): USD 80-200/ton (variable concentrations, process integration challenges)

• Chemical/petrochemical: USD 70-180/ton depending on specific process and CO₂ characteristics

• Direct air capture: USD 200-600/ton currently (410 ppm atmospheric concentration, massive throughput needs)

Transport Costs:

• Pipeline (new construction): USD 50,000-150,000 per km capital, USD 2-5/ton per 100 km operational

• Pipeline (repurposed existing): USD 5,000-15,000 per km capital, similar operational costs

• Marine transport (short distance <500 km): USD 10-30/ton including loading/unloading

• Marine transport (regional 1,000-3,000 km): USD 30-80/ton for dedicated CO₂ carriers

• Rail or truck: USD 50-150/ton limited to small volumes and short distances

• Compression for transport: 100-150 bar pressure, 60-70% of pipeline transport costs

• Liquefaction for shipping: -50°C at 7 bar or -30°C at 15 bar, additional energy requirements

• Infrastructure amortization: 20-30 year economic life spreading capital costs

Storage Costs:

• Depleted oil/gas reservoir: USD 5-20/ton (characterized geology, existing wells, proven sealing)

• Deep saline aquifer: USD 10-30/ton (exploration drilling, characterization, uncertainty)

• Onshore storage: USD 5-15/ton lower costs versus offshore

• Offshore storage: USD 15-30/ton higher well costs, marine logistics, monitoring

• Well drilling: USD 5-20 million per injection well depending on depth (1,000-3,000 m) and location

• Well count: 5-10 wells for 30-50 million ton capacity over 20-30 years

• Monitoring systems: USD 5-15 million capital, USD 0.5-2 million annual operational

• Post-closure surveillance: 10 years under Indonesia regulations, USD 1-5 million total

Total System Costs (Integrated Projects):

• Natural gas processing CCS: USD 40-90/ton total system (capture + transport + storage)

• Power generation CCS: USD 70-150/ton total depending on fuel type and configuration

• Industrial CCS: USD 100-220/ton varying by sector and capture complexity

• Cross-border regional hub: USD 80-180/ton including international transport premium

• Economies of scale: 50%+ cost reduction from 1 million ton/year to 5+ million ton/year projects

• Learning curve: 10-20% cost reduction per doubling cumulative capacity historically

• Competitiveness threshold: Requires carbon price USD 80-120/ton or equivalent subsidy without revenue offsets

• EOR integration: Can reduce net cost to USD 10-40/ton or achieve profitability depending on oil prices

Storage costs prove relatively modest USD 5-30 per ton compared to capture and transport given geological formations provide essentially free disposal capacity once accessed, with expenses primarily comprising well drilling (USD 5-20 million per injection well depending on depth and location), injection facilities (compression, manifolds, controls), and monitoring systems (seismic surveys, pressure sensors, geochemical sampling). Depleted oil and gas reservoirs offer lowest storage costs USD 5-20 per ton benefiting from characterization data, potentially reusable wells, and proven sealing demonstrated through hydrocarbon retention, though limited capacity compared to deep saline aquifers requiring exploration drilling and characterization adding USD 10-30 per ton. Onshore storage generally costs less than offshore given simpler logistics and lower well costs, though offshore locations often provide proximity to coastal industrial emitters and enable marine CO₂ import infrastructure supporting regional hub business models justifying incremental expenses.

Integrated CCS project economics combining all cost components indicate total levelized costs ranging USD 40-90 per ton for natural gas processing (optimal initial applications), USD 70-150 per ton for power generation, and USD 100-220 per ton for industrial sources before considering revenue offsets from EOR, carbon credits, or government incentives. These costs require either carbon pricing mechanisms (carbon taxes, emissions trading systems) establishing comparable costs for unabated emissions, regulatory mandates requiring emissions reductions regardless of costs, or direct government subsidies covering cost differentials making CCS competitive with business-as-usual operations. Current carbon prices in European Union ETS (approximately EUR 80-100 per ton or USD 85-110) approach competitiveness thresholds for power generation and some industrial applications, while voluntary carbon markets paying USD 50-200+ per ton for high-quality permanent removal credits provide alternative monetization pathways particularly attractive for storage-as-a-service business models serving corporate net-zero commitments.

Scale economics prove determining factor with 50% or greater cost reductions achievable increasing capture capacity from 1 million ton per year (small commercial scale) to 5+ million tons (large scale) through fixed cost amortization, equipment optimization, and operational learning. Hub development leveraging shared infrastructure across multiple emitters captures these economies while reducing individual project risks through diversified revenue sources and flexible capacity utilization. Indonesia's positioning emphasizing regional hubs at Asri Basin, Kutai Basin, and ONWJ aligns with scale economic principles, targeting multi-gigaton capacities serving dozens potential emitters domestically and internationally rather than isolated single-source projects facing higher costs and concentrated risks. Technology learning curves historically demonstrate 10-20% cost reductions per doubling cumulative capacity as industries mature, optimize designs, standardize equipment, develop specialized supply chains, and accumulate operational experience, suggesting current costs substantially declining as global CCUS deployment accelerates from present 50 million ton per year to hundreds of millions required achieving climate targets.

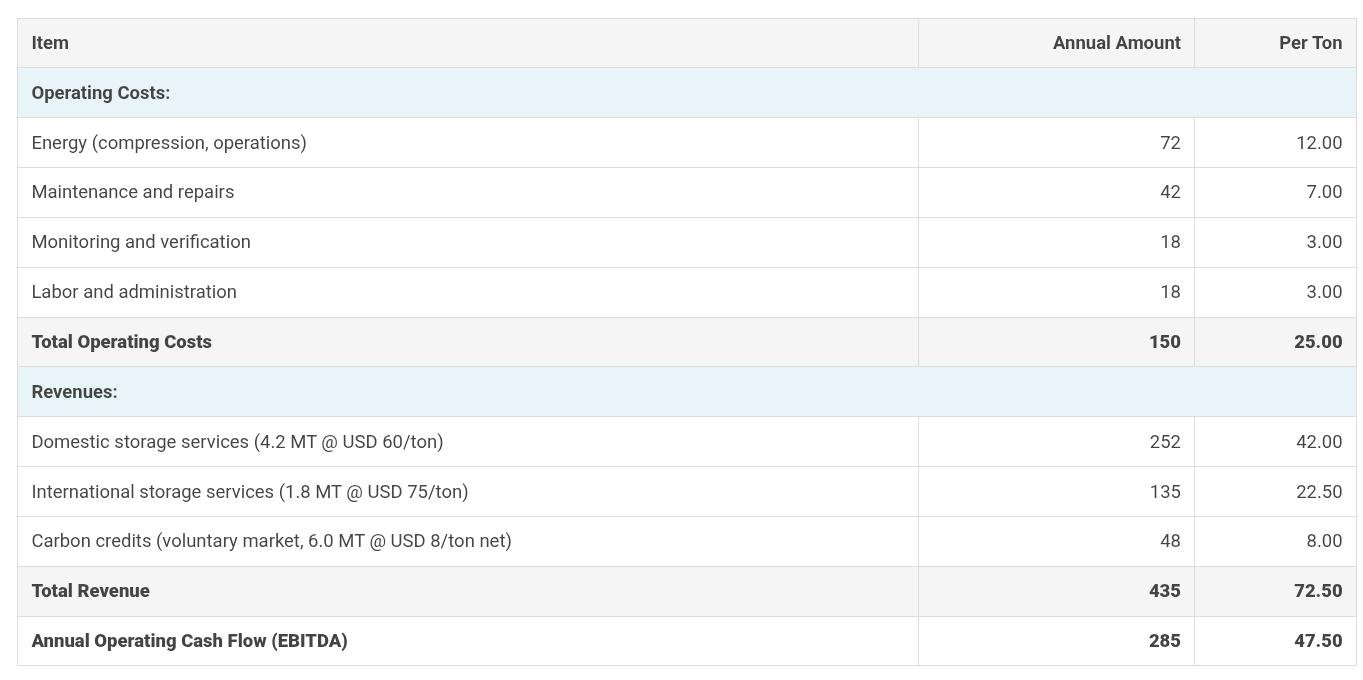

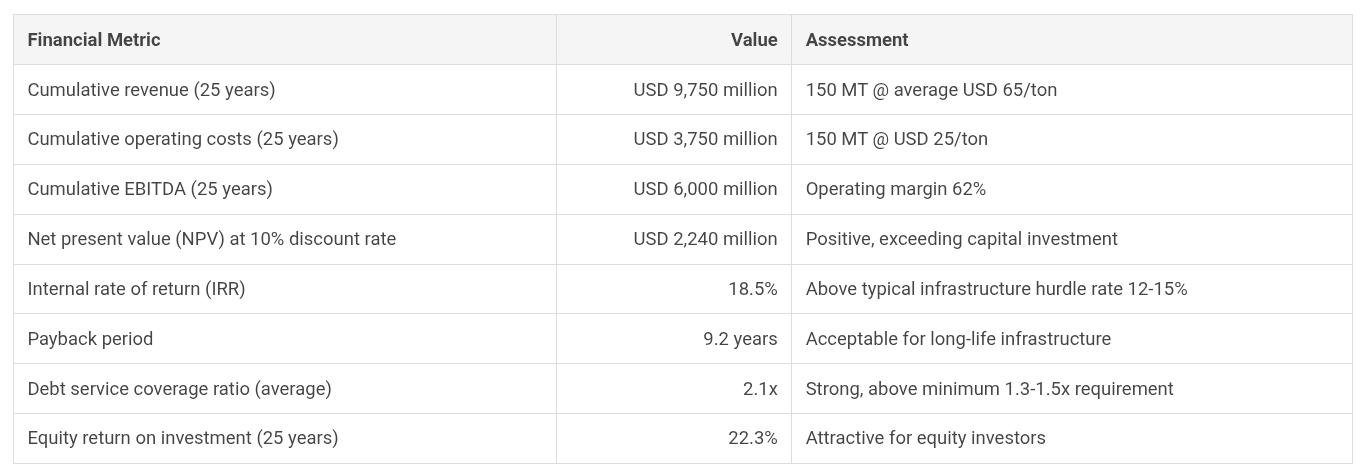

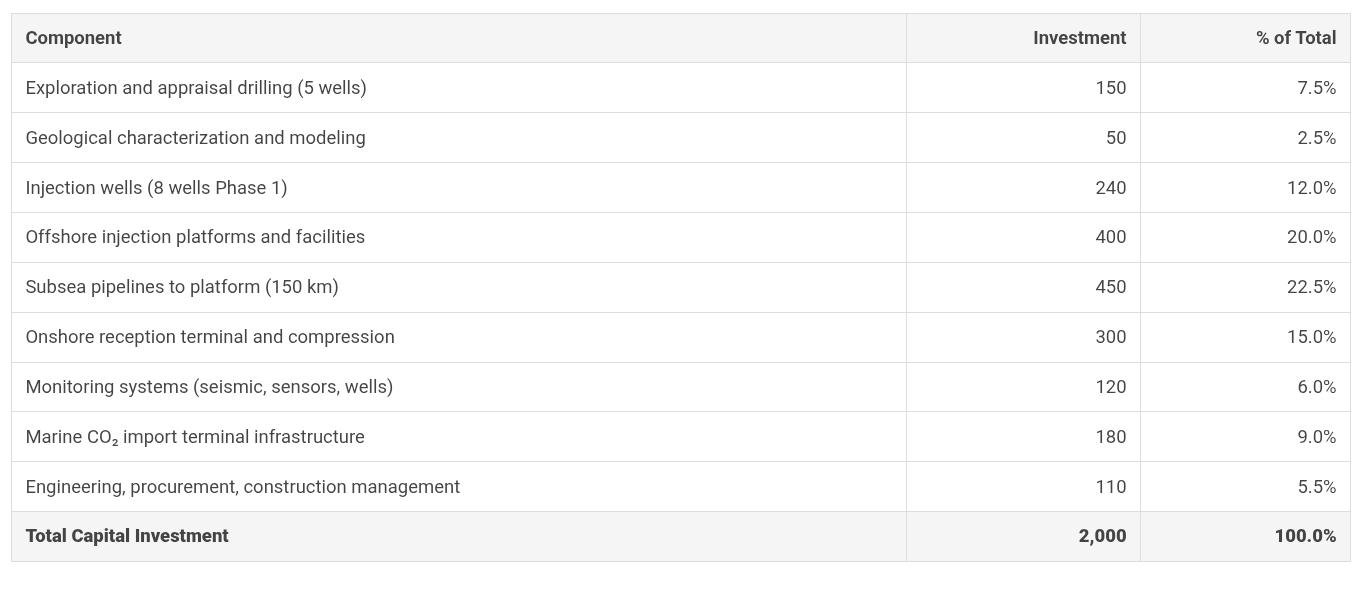

Economic Case Study: Asri Basin CCS Hub Financial Analysis

Project Parameters and Assumptions:

Storage capacity: 3.0 gigatons total geological capacity

Operational capacity: 30 million tons per year CO₂ injection (100-year theoretical capacity)

Phase 1 development: 150 million tons over 25 years (6 million tons/year average)

Capital investment: USD 2 billion including capture, transport, injection, monitoring infrastructure

Operational expenditure: USD 25/ton including energy, maintenance, monitoring, labor

Revenue model: Storage service fees USD 65/ton (domestic USD 60, international USD 75 weighted average)

Capacity allocation: 70% domestic industrial emitters, 30% international sources (Singapore, Korea, Japan)

Financial structure: 40% equity (Pertamina, ExxonMobil, KNOC), 60% project finance debt at 7% interest, 25-year project life

Capital Investment Breakdown (USD Millions):

Project Financial Returns Analysis (25-Year Projection):

Financial Viability Conclusion:

Analysis demonstrates Asri Basin CCS Hub achieves commercial viability under assumed storage fee structure (USD 60-75 per ton) without requiring government operational subsidies, though project depends on achieving contractual commitments for capacity utilization and maintaining cost discipline during construction and operations. Financial returns exceed typical infrastructure project thresholds with 18.5% IRR and positive NPV supporting investment by partners Pertamina, ExxonMobil, and KNOC. Key success factors include securing long-term storage contracts with domestic and international emitters before final investment decision, optimizing capital costs through experienced contractors and equipment standardization, managing operational efficiency achieving assumed USD 25 per ton costs, and establishing favorable fiscal treatment under Indonesian regulations including cost recovery provisions for PSC-related activities and tax incentives for CCS infrastructure. Sensitivity analysis indicates project remains viable with 15-20% revenue reductions or cost increases, providing reasonable buffer against market uncertainties and operational challenges typical for first-of-kind regional hub development.

Cross-Border CCS Collaboration: Regional Hub Development

Indonesia's geological storage advantages combined with neighboring countries' emissions challenges and limited domestic storage capacity create compelling rationale for cross-border CO₂ transport and storage serving regional decarbonization requirements. Singapore generates approximately 50 million tons annual CO₂ emissions from power generation, refining, petrochemicals, and other industrial activities while possessing virtually no suitable geological storage given 733 square kilometer land area and shallow geology unsuitable for permanent CO₂ sequestration. Climate commitments targeting 65% emissions reduction by 2050 require substantial decarbonization technologies including hydrogen adoption, electrification, and CCS for residual hard-to-abate emissions, necessitating international storage solutions absent domestic alternatives. Japan emits approximately 1.1 billion tons annually with limited onshore storage though potential offshore capacity in Sea of Japan sedimentary basins requiring significant development, while South Korea's 650 million ton annual emissions face similar constraints with limited domestic geological options.

Indonesia-Singapore CCS partnership represents most advanced cross-border framework with governments signing Letter of Intent 2024 committing negotiate legally binding bilateral agreement enabling CO₂ export from Singapore to Indonesian storage facilities. Framework addresses complex issues including international legal liability for stored CO₂, customs and border procedures for CO₂ shipments, monitoring and verification protocols acceptable to both jurisdictions, financial mechanisms ensuring storage permanence, and dispute resolution procedures governing multi-decade agreements outlasting typical government terms. Singapore's proximity to Indonesian storage sites (Asri Basin approximately 400 kilometers from Singapore, reachable via marine transport at USD 25-40 per ton) provides cost-competitive solution compared to theoretical domestic storage requiring extensive offshore exploration uncertain yielding adequate capacity. Singapore Ministry of Sustainability and Environment actively engaging CCS providers globally while Indonesian government sees substantial revenue opportunity potentially storing 10-20 million tons annually from Singapore generating USD 600 million to USD 1.5 billion annual storage service fees.

Cross-Border CCS Framework Elements:

Indonesia-Singapore Bilateral Agreement (Under Negotiation):

• Legal foundation: Letter of Intent signed 2024, binding agreement targeted 2025-2026

• Scope: Framework enabling CO₂ export from Singapore to Indonesian storage sites

• Volume potential: 10-20 million tons per year from Singapore industrial emitters

• Storage locations: Asri Basin (nearest at 400 km), other basins as capacity develops

• Transport mode: Marine using specialized CO₂ carriers, potential pipeline if volumes justify

• Storage fees: Estimated USD 60-80 per ton competitive with alternative international options

• Liability provisions: Long-term stewardship transfer mechanisms after closure verification

• Regulatory harmonization: Monitoring standards, reporting requirements, verification protocols

South Korea Participation (KNOC in Asri Basin):

• Partnership: KNOC signed framework agreement with Pertamina and ExxonMobil for Asri Basin

• Purpose: Potential South Korean industrial CO₂ injection into shared storage infrastructure

• Korean emissions: 650 million tons annual with limited domestic storage options

• Policy drivers: Carbon neutrality by 2050 requiring substantial CCS deployment

• Technology collaboration: Korean engineering companies, shipping expertise, project finance

• Government support: Korean carbon pricing system creating compliance demand

• Volume potential: 5-15 million tons per year from Korean heavy industries

• Economic benefit: Indonesia receives storage fees, Korea achieves climate targets

Japan Collaboration (Multiple Projects):

• Tangguh: bp partnered with Chubu Electric Power exploring CCS value chain Japan-Indonesia

• Gundih: Japanese entities JOGMEC, JGC, J-Power, JANUS collaborating with Pertamina

• METI support: Japan Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry funding feasibility studies

• Japanese emissions: 1.1 billion tons annual requiring massive CCS deployment for net-zero 2050

• Offshore potential: Japan's domestic sea bed storage under development but limited capacity

• LCO₂ shipping: Japan possesses advanced marine transport capability for CO₂ carriers

• Technology transfer: Japanese engineering expertise, equipment, project management

• Financial participation: Development finance, commercial investment, offtake agreements

Legal and Regulatory Framework Requirements:

• London Protocol: 2009 amendment permitting cross-border CO₂ transport for storage (Indonesia ratification needed)

• National legislation: Host country laws enabling foreign CO₂ imports (Indonesia PR 14/2024 provides 30% allocation)

• Liability provisions: Clear assignment of long-term stewardship responsibilities

• Monitoring standards: Internationally compatible measurement, reporting, verification protocols

• Environmental assessment: Transboundary impact evaluation, public consultation procedures

• Customs procedures: CO₂ classification, inspection requirements, documentation standards

• Financial guarantees: Bonding or insurance ensuring storage permanence and liability coverage

• Dispute resolution: International arbitration mechanisms for long-duration agreements

Japan's participation through multiple channels including Chubu Electric's Tangguh collaboration and METI-supported Gundih project demonstrates substantial interest leveraging Indonesia's geological advantages addressing domestic constraints. Japan Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry allocated significant funding supporting feasibility studies, technology development, and pilot demonstrations throughout Asia recognizing CCS necessity achieving 2050 carbon neutrality commitments while maintaining industrial competitiveness. Japanese engineering companies and equipment manufacturers possess world-leading capabilities in capture technologies, offshore development, marine transport, and monitoring systems creating mutually beneficial partnerships where Japan provides technology and expertise while Indonesia offers geological storage and operational infrastructure. Potential volumes from Japan could reach 20-50 million tons annually from LNG terminals, refineries, power plants, and industrial facilities along coastal areas facing domestic storage limitations and regulatory pressures mandating emissions reductions.

Regional hub business model envisions Indonesia providing storage-as-a-service to multiple regional emitters through shared infrastructure optimizing costs and flexibility. Pertamina International Shipping developing specialized LCO₂ carrier fleet and reception terminal capabilities creates essential transport infrastructure connecting regional sources to Indonesian storage sites, with ship-based transport offering flexibility serving multiple origins and destinations compared to fixed pipelines requiring dedicated point-to-point connections. Hub-and-spoke configuration positions coastal reception terminals accepting marine CO₂ deliveries from Singapore, Malaysia, Japan, and Korea, connecting via pipeline networks to offshore storage platforms serving multiple injection sites across geological basins, enabling capacity additions responding to market growth and providing operational redundancy improving reliability. Total regional addressable market potentially exceeds 100 million tons annually considering combined emissions from Singapore, South Korea, Japan, and other Southeast Asian nations lacking adequate domestic storage, representing multi-billion dollar annual revenue opportunity for Indonesia's CCS industry if supportive policies and infrastructure investments materialize.

Frequently Asked Questions About Carbon Capture and Storage in Indonesia

1. How does Indonesia's 400-600 gigaton storage capacity compare to regional and global requirements?

Indonesia's estimated 400-600 gigaton geological storage capacity positions nation among largest potential CCS providers globally, exceeding by orders of magnitude projected regional requirements through 2060 even under aggressive decarbonization scenarios. For perspective, International Energy Agency Clean Technology Scenario requires cumulative 107 gigatons CO₂ permanently stored globally through 2060, meaning Indonesia's capacity theoretically accommodates four-to-six times entire global requirement though practical limitations including site characterization, infrastructure development, and economic viability constrain actually accessible portion. Asia-Pacific region including Indonesia, Australia, China, India, Japan, and Southeast Asian nations emits approximately 18 billion tons CO₂ annually with hard-to-abate sectors potentially requiring 1-3 billion tons annual CCS by 2050, implying Indonesia's capacity could theoretically serve regional requirements for centuries. However, capacity represents geological potential rather than immediately deployable infrastructure, with actual utilization depending on site-by-site development, permitting, financing, and commercial arrangements determining pace and scale of deployment over coming decades.

2. What distinguishes CCS from CCUS and why does terminology matter for Indonesian projects?

Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) refers specifically to capturing CO₂ from emission sources or atmosphere and permanently storing underground in geological formations without intermediate utilization, achieving direct emissions reduction or atmospheric carbon removal. Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage (CCUS) encompasses broader range including using captured CO₂ in industrial processes or products before any remaining CO₂ undergoes permanent storage, with utilization pathways including enhanced oil recovery, chemical manufacturing (methanol, plastics), building materials (carbonated concrete), and greenhouse agriculture. Distinction matters significantly for Indonesian regulatory framework since MEMR Regulation 2/2023 differentiates treatment: CCS activities receive straightforward operational cost recovery under PSCs while CCUS involving EOR or other revenue-generating utilization requires more complex accounting separating storage costs from production revenue. Additionally, carbon credit eligibility differs with pure CCS generally receiving full credit for captured volumes while CCUS credits may require lifecycle analysis demonstrating net emissions reduction accounting for utilization pathway emissions. Enhanced oil recovery particularly requires careful analysis since CO₂ enables additional oil production generating combustion emissions potentially offsetting storage climate benefits, though Pertamina's trials demonstrating 40-60% CO₂ retention indicates substantial net carbon reduction especially when displacing new exploration and production. Projects should clearly distinguish CCS versus CCUS applications from outset given regulatory, financial, and environmental assessment implications affecting project structure and economics.

3. How do MEMR Regulation 2/2023 and Presidential Regulation 14/2024 differ in scope and applicability?

MEMR Regulation 2/2023 issued March 2023 specifically governs CCS and CCUS implementation within existing upstream oil and gas working areas operated under production sharing contracts (PSCs) with SKK Migas or BPMA, enabling PSC contractors leverage geological knowledge, existing infrastructure, and established regulatory relationships facilitating deployment. Regulation provides detailed operational requirements including development planning, technical standards, monitoring obligations, and cost recovery provisions allowing contractors treat CCS operational expenses as recoverable costs under PSC terms, creating favorable economics but limiting participation to entities holding upstream oil and gas rights. Presidential Regulation 14/2024 enacted January 2024 serves as umbrella framework establishing broader national policy covering CCS activities anywhere in Indonesia whether within PSC areas or designated carbon storage permit areas (WIPK), enabling participation by non-PSC entities including independent storage providers, power generators, industrial emitters, and international partners establishing Indonesian operations. PR 14/2024 establishes high-level policy principles, institutional authorities, cross-border provisions, and directions for subordinate regulations while MEMR 2/2023 provides specific technical implementation details for PSC context. Subsequently, MEMR Regulation 16/2024 effective December 2024 implements PR 14/2024 by establishing detailed procedures for WIPK designation, exploration and storage operation permits, tender processes, and technical requirements for entities operating outside PSC framework. These three regulations form hierarchical structure with PR 14/2024 providing overall policy, MEMR 2/2023 governing PSC applications, and MEMR 16/2024 enabling independent carbon storage operations, together creating comprehensive framework accommodating diverse business models and participants.

4. What technical and financial capabilities do entities need for participating in Indonesian CCS tenders?

MEMR Regulation 16/2024 establishes prequalification requirements for WIPK carbon storage permit area tenders emphasizing demonstrated technical and financial capabilities in oil and gas, mining, geothermal, or CCS sectors. Technical requirements include geological characterization expertise through previous exploration experience, reservoir engineering capabilities for storage capacity assessment and injection optimization, well drilling and completion expertise ensuring safe operations, monitoring technology proficiency for verification and environmental protection, and project management track record delivering complex energy infrastructure on schedule and budget. Financial capabilities require demonstrating sufficient capital for exploration commitments (typically USD 10-50 million depending on area size and complexity), ability to secure project financing for development phase (hundreds of millions to billions for major hubs), working capital for sustained operations, and financial guarantees or bonding covering long-term monitoring and potential remediation obligations. Entities meeting prequalification criteria join MEMR shortlist receiving preferential treatment in subsequent tenders including invitation to direct selection processes and streamlined evaluation focusing on exploration work commitments rather than requiring recertification of financial and technical capabilities. Consortium structures explicitly permitted combining complementary strengths (e.g., international major providing technical expertise and project finance partnering with Indonesian entity possessing local knowledge and relationships), though requiring clear delineation of management responsibilities and liability allocation. Foreign entities must establish Indonesian presence through incorporated entity or permanent establishment for permit holding, creating opportunities for joint ventures, license agreements, or management contracts structuring international participation while satisfying local content and technology transfer objectives supporting Indonesian CCS industry development.

5. How will Indonesia handle long-term liability for stored CO₂ after project closure?

Presidential Regulation 14/2024 establishes framework where CCS operators bear responsibility for monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) activities throughout operational period and continuing 10 years following closure, after which liability transfers to Indonesian government through MEMR and Directorate General of Oil & Gas assuming responsibility for long-term stewardship. Ten-year post-closure monitoring requirement aims demonstrating storage permanence through plume stability confirmation, formation pressure dissipation, absence of detectable leakage, and groundwater quality protection before government acceptance. Operators must reserve financial provisions (bonds, trusts, or other security mechanisms) covering anticipated monitoring costs and potential remediation needs during this period, preventing orphaned sites requiring government expenditure if operators default or dissolve. However, regulations stop short of explicitly stating government assumes all liability for CO₂ leakage occurring after post-closure period expires, creating uncertainty potentially concerning project developers, lenders, and international partners seeking definitive liability closure enabling removal of provisions from balance sheets and termination of insurance coverage. International precedents including Norway's petroleum regulations and Alberta's Carbon Capture and Storage Liability Management Framework provide models for explicit liability transfer with government assumption of perpetual stewardship responsibilities following rigorous site assessment and financial security receipt, though these developed-nation frameworks may require adaptation to Indonesian institutional context and fiscal constraints. Clarity on final liability allocation proves necessary attracting international investment in storage-as-a-service business models where long-term uncapped liability exposure could render projects unfinanceable or require risk premiums substantially increasing costs. Forthcoming implementing regulations expected address these details establishing procedures for closure certification, financial adequacy determination, transfer documentation, and government institutional arrangements managing transferred liabilities perpetually without creating unreasonable future fiscal burdens.

6. What carbon pricing mechanisms or incentives will support commercial CCS viability in Indonesia?

Indonesia currently lacks comprehensive carbon pricing mechanism comparable to European Union ETS or California's cap-and-trade system creating direct compliance value for emissions reductions, though Taxation Harmonization Law 7/2021 establishes legal foundation for carbon tax with rates and implementation details subject to government regulation not yet fully implemented. Initial carbon tax proposals suggest starting rate approximately USD 2-5 per ton CO₂ for coal-fired power generation (lowest internationally and insufficient driving CCS adoption given typical costs USD 70-150 per ton for power applications), with intentions increasing rates progressively toward levels incentivizing emissions reduction investments. Government developing broader emissions trading system potentially including power sector, heavy industry, and eventually transportation, though timeline and design details remain under discussion with stakeholders. Without meaningful carbon price near-term, Indonesian CCS development depends on alternative incentives including PSC cost recovery provisions under MEMR 2/2023 enabling upstream contractors treat CCS as operational expense, capital grants or subsidies for demonstration projects (potential development finance from World Bank, Asian Development Bank, or bilateral sources), tax incentives including holidays and accelerated depreciation under investment regulations, international carbon credit revenues from voluntary markets (potentially USD 50-200 per ton for high-quality permanent removal), cross-border storage service fees (USD 60-80 per ton for regional emitters), enhanced oil recovery revenue offsets, and regulatory mandates eventually requiring industrial emissions reductions regardless of costs. Pertamina's multiple project development suggests state enterprise willing accept below-market returns on initial investments recognizing strategic positioning benefits and eventual commercial viability as carbon pricing matures, while international partners including ExxonMobil, bp, and Asian entities participate partly anticipating future policy development creating favorable economics and partly securing first-mover advantages in emerging market. Government statements emphasize commitment achieving net-zero 2060 and 29% reduction by 2030 suggest eventual carbon pricing or regulatory mechanisms necessary drive substantial CCS deployment supporting climate commitments, though detailed implementation remains work in progress requiring stakeholder consultation, administrative capacity building, and political consensus.

7. How does Indonesia's CCS development timeline compare to global leaders like Norway and United States?

Indonesia's CCS development follows accelerated trajectory compared to global pioneers though starting from later baseline, with comprehensive regulatory framework established 2023-2024 versus Norway's decades-long incremental development beginning 1990s and United States' gradual evolution through enhanced oil recovery applications before climate-focused policies. Norway operates world's longest-running dedicated storage project (Sleipner field capturing 1 million tons annually since 1996 from natural gas processing) and recently launched Longship full-chain CCUS covering Norcem cement plant capture, transport infrastructure, and offshore storage in Northern Lights project accepting international CO₂ from 2024. United States possesses over 8,000 kilometers CO₂ pipelines and 50+ operational CCS projects primarily serving EOR applications, with recent 45Q tax credit expansion stimulating new wave climate-focused storage projects including massive Gulf Coast Blue hydrogen facilities and industrial capture initiatives. Indonesia's regulatory advancement within 2-3 years establishing frameworks enabling both PSC and independent storage operations represents rapid policy development potentially enabling faster deployment once initial projects demonstrate technical and commercial viability. However, actual operational capacity lags global leaders with Indonesia's first large-scale projects (Tangguh, Asri Basin) targeting late 2020s commissioning versus Norway and US decades operational experience, and technical capacity requiring substantial development through pilot projects, workforce training, supply chain establishment, and learning-by-doing addressing Indonesia-specific geological and operational challenges. Indonesia's strategic advantages include newer regulatory framework potentially avoiding legacy limitations in mature jurisdictions, substantial untapped storage capacity not constrained by existing utilization, and regional market opportunity serving neighboring nations' demands creating scale enabling faster cost reduction through experience curves. If Indonesian government maintains policy commitment, streamlines permitting without sacrificing environmental rigor, attracts continued international partnership bringing technology and finance, and successfully launches initial flagship projects demonstrating capability, Indonesia could plausibly emerge as Asia-Pacific CCS leader within 10-15 years comparable to Norway's current position in Europe, though sustained execution over extended period necessary converting potential to realized capacity and establishing reputation supporting commercial-scale industry.

8. What role can CCS play in Indonesia's broader energy transition beyond fossil fuel sectors?